INTERVIEW

Learning to Unlearn with Dr. Emily Contois

WORDS BY SARAH COOKE

GRAPHICS BY CLARE LAGOMARSINO

PHOTOS COURTESY OF EMILY CONTOIS

MAY 6, 2021

Academia with urgency—that is, with an aim to engage the world—is exactly what Dr. Emily Contois provides not only in Diners, Dudes, & Diets, but in the broader scope of how she approaches her work. With expansive curiosity, Dr. Contois brings together narratives around food, identity, and power, illuminates how they perpetuate harm, and arms us with the awareness that actually, it is possible for things to be better.

This interview, held on March 30, 2021, has been condensed and edited for clarity.

On your phone or short on time? Catch the snackable version on IG stories.

When did you start thinking about diners, dudes, and their diets, and at what point did you realize you had a book?

I started with diet culture when I was 20 years old, writing my undergrad thesis after I’d done the work on myself trying to recover from an eating disorder, and seeing how close the venn diagram was of diet culture, what was an actual eating disorder, and what was sometimes government dietary advice.

I loved writing, I loved research, but I just was so nervous that it wasn’t going to make enough of a difference in the world. I didn’t feel like being a writer or a professor was something that I could entertain; I needed to do something.

Public health felt like the space where I could help people think about the way they eat and about what health means, so I took a little detour to public health school and worked for five years in commercial worksite wellness.

Then I went back into the academy. I got a master’s in gastronomy from the program at Boston University founded by Julia Child and Jaques Pepin. When I did my thesis there, that’s when I picked up this research again. It was in this moment where I was looking at things like Atkins, South Beach, and the Zone diet. Because of the actual foods that you eat on a low-carb diet, men follow them, too. You can eat the burger, the bacon, and the cheese; you just don’t get the bun. You weren’t expected to eat just salads, like so much of the low-fat dogma coming out of the diet industry and public health.

Books for research and teaching

When I was applying to go to school for my PhD, that’s what I pitched as what I would do as a doctoral student: a shift in the gender dynamics of dieting. My PhD was in American Studies, where you read really deeply across lots of fields. I could go back and study American cultural history since the late nineteenth century through this lens of consumer culture and media.

Doing this research, I knew there was a book there. (You have to write a dissertation for your PhD; then, if you want to get tenure, you have to write a book.) I knew there was a story to be told that could have influence in the academy and then hopefully for general readers as well, everyday folks that are thinking about their food media environments.

The parallels you were just saying about diet culture and the way that disordered eating get seen as the “bad” side, while diet culture is praised—they have so many similar tenets, so much similar language. If you are eating low carb as a woman, that means maybe something is wrong; you’re not the Cool Girl from Gone Girl¹. But then if you go for the swiss chard burger as a guy, you’re the cool bro, you’re doing it for the gains.

¹In Gillian Flynn's novel Gone Girl, the character Amy talks about this trope. She says: "Men always say that as the defining compliment, don’t they? She’s a cool girl. Being the Cool Girl means I am a hot, brilliant, funny woman who adores football, poker, dirty jokes, and burping, who plays video games, drinks cheap beer, loves threesomes and anal sex, and jams hot dogs and hamburgers into her mouth like she’s hosting the world’s biggest culinary gang bang while somehow maintaining a size 2. Men actually think this girl exists."

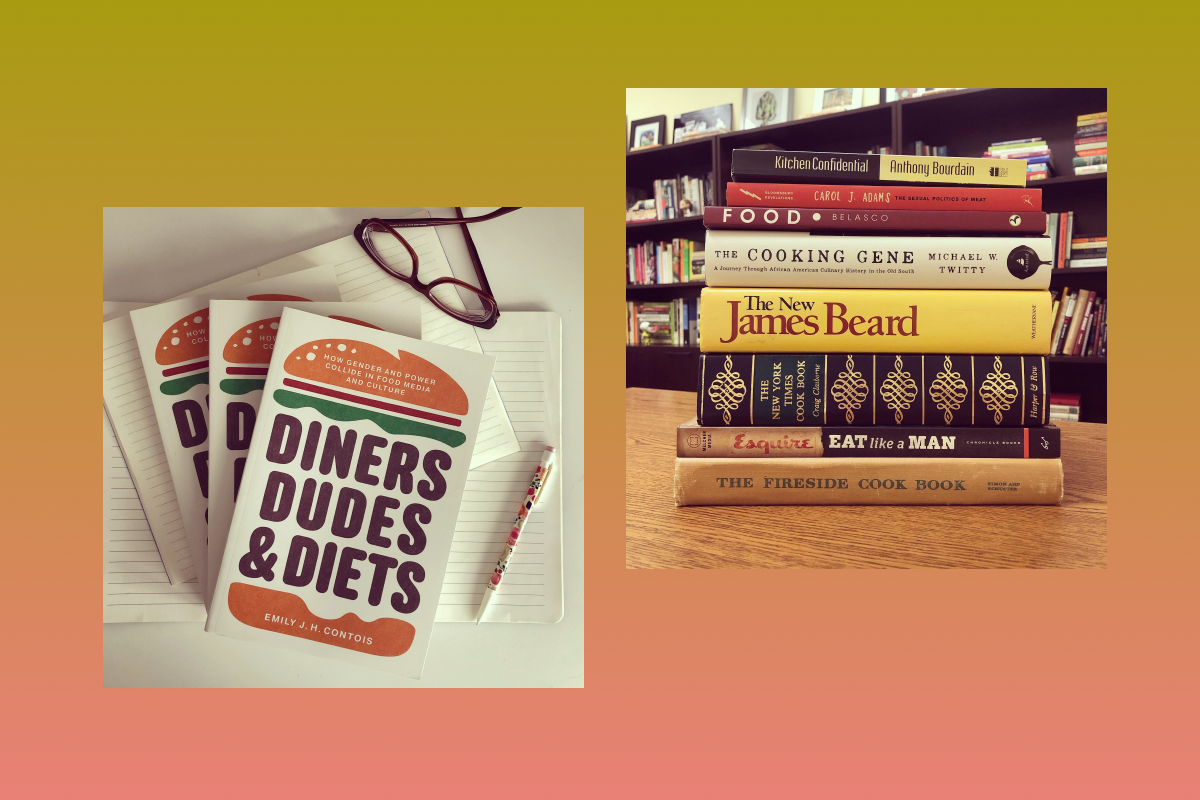

Left: Diners, Dudes & Diets, Emily's first book; Right: Book stack for week 1 of Emily's Food Media class

What expectations did you have starting research for the book, and how were they met or challenged?

I did an inductive process, where I read broadly and looked at evidence across all different areas of culture. I looked at everything from diet books to menus to cookbook headnotes to ingredients to Instagram. I did all of that to see what were the patterns, what were the stories, what were the tactics coming up again and again.

There was this idea of hegemonic masculinity, this dominant way of being a man at a particular time in a particular place. At first, that’s what I was seeing: just these conventions, these stereotypes, these norms about masculinity to be able to sell food and speak to men in this way.

But as I kept looking, it wasn’t quite that. The Dude is something unique and different, in that it has this slacker quality that’s being embraced, and so in that way, the investment with food is so insincere and uninvested that it never impinges on the prowess and authority of masculinity itself.

It was interesting to start with dieting and have it grow from there to cookbooks and food television and food marketing and particular food product categories. You can see different layers of how gender and hierarchy and inequity are at so many different spots throughout our food media ecosystem.

In the book, part of what I’m critiquing is this binary application of gender onto our food world, that it’s either masculine or it’s feminine. That strict binary, which doesn’t exist, has been replicated and repeated so much, and it does so much damage.

A guy wrote a review of the book where he said I should have had more generosity in my reading of how this gender trope works. [The Dude] is within the context of the Great Recession, which was this horrible, difficult moment for everyone, and especially for men. How do you figure out who you are as a man, when being a man is so tied in our culture to things like breadwinning and professional success and owning a home and supporting your family?

There’s a part of the book where I talk about the dad bod and how that gave some flexibility to some men to move through the world without that pressure to be chiseled and lean and have six-pack abs. But that did nothing for women’s bodies or for actual mom’s bodies. And that’s why I sort of put up my hands, like, “It was a generous read!” [Both laugh.] I gave it everything I could. Just say that patriarchy screws all of us, but not equitably. Some of us just suffer more under that system.

Writing and revising Diners, Dudes & Diets

In general, do you find that reviews are giving you the generous read?

I think so far the readers I’ve had are on board with the argument. I got trolled pretty badly in 2018 when I wrote about Hot Ones, so I knew that there would be a section of the readership for whom this idea—that gender is a social and cultural construction that doesn’t naturally exist in us but it comes to us through our culture—would be difficult. I knew there were folks for whom that was a totally alien idea, one that they weren’t willing to accept or just didn’t have the tools.

I remember the first time somebody pushed back in college when I said something about women are meant to be naturally nurturing, that we’re meant to be mommies. At 18, I believed that, because my mom was such a natural mom! [Both laugh.] So I get it.

I’ve experienced that menu of negative responses from confusion to pushing back to just the out-right trolling, which is a game and has nothing to do with the actual ideas. But the book itself, so far, maybe because it’s a little academic book [Emily laughs], it hasn’t met that big of attention, so it hasn’t come up with a lot of negative reactions.

I wrote an op-ed for NBC News on Thanksgiving Day about how we can sort of relax the patriarchy and all have a better day. A couple of guys reached out after that who were not pleased with the idea, which was funny, because I hadn’t written it as “Smash the Patriarchy!” [Sarah laughs.] It was like, how to have men not be held up to these unreasonable expectations.

I think with the dad bod, it’s a socially accepted but more beloved thing than a mom bod, because the whole point of the mommy bod is that you lose it². The covers you see on Us Weekly and People: How Did She Do It! It’s like, she hired a trainer and probably ate really horribly. There is an obvious way she did it, and it’s usually not a good one.

²In 2019, Us Weekly framed an article about rapid weight loss as a celebration of new celebrity mothers and their ability to lose weight.

"Despite appearances, celebrity moms are mere mortals with real bodies just like the rest of Us... No matter the methods employed, losing the baby weight is hard work. And Us salutes the brave Hollywood women who have debuted their post-baby body transformations in 2019."

Photo: KC Hysmith

I wanted to ask about an interview you did with Anne Helen Petersen. You said, “The ability to eat well in the United States is to be able to eat meat regularly.” I have two questions about that. What do you think would have to happen for that definition of eating well to change? Do you see a vegetarian and/or vegan corollary to The Dude?

I’ll start with the second one, because part of the problems of marketing veganism or vegetarianism as a lifestyle, or some of these plant-based protein products, is this fact that Carol J. Adams writes so perfectly in her work of feminist-ecocriticism: that to eat meat is part of what constructs and makes masculinity.

When you break down that formula, there’s this cultural negotiation that has to take place. For some men, particularly ones who lean more conservatively, that’s a big ask. I’ve been so fascinated in the eighteen months of seeing this idea that the Left or the progressives are coming for your meat. [Sarah laughs.] That’s been taken up quite seriously. It’s not even a joke, but this real fear that as we face—I don’t even say climate change anymore, I say a changed climate in crisis, that’s where we are—what those steps need to be for individuals, but more importantly at this level of big institutions, governments, and international cooperation agreements moving forward.

Thinking about our agricultural space and animals in particular as one piece of this puzzle, that resistance to change is in part tied up with these ideas of masculine supremacy, white supremacy, a middle-class orthodoxy. It’s a really complicated resistance that’s then layered over a particular political ideology and point of view at this moment.

And so to your first question, I’m so afraid that something really terrible is going to have to happen before people can reconcile all of that. Living in Oklahoma, the summers here are so much hotter than they were fifty years ago; I can’t imagine living here without the electricity-sucking air conditioning. I know that’s what it’s like elsewhere in the world.

As we think about how to live comfortably on this planet—when we think about the fires, when we think about changing weather patterns and patterns of extreme weather events—I wonder in pockets where people are facing this if maybe there’s a changing attitude among more affluent people. We know from the environmental justice perspective, from a climate justice and food justice perspective, that those with the least access and the least amount of resources are the ones who are going to be affected first.

So sadly, I think it’s when people with lots of privilege and used to having this easy, happy life don’t have it anymore. Maybe then, that’s when stuff will start to speed up.

Spring blooms

I think there’s an element of the plant-based masculinity that feels very Dude-like, but instead of being distanced from their food, they’re evangelical about Impossible. It still feels like there’s a distance from the fact of what food is, which is human labor.

When I kept coming back to The Dude, it’s a privileged role and a privileged status to not care and say whatever and slack off and just opt out. He isn’t really committed to any sort of social change or collective action, and maybe it’s too much to expect from him. I think what’s been hard with these plant-based solutions and how much investment is behind them is that we’re again turning to the market for these technological fixes to our food system that’s broken for a lot of more complex reasons than that.

It goes all the way back to the history of vegetarianism in England and the United States: the idea that we’re always trying to replicate the animal in whatever vegetarian, vegan option we’re putting forth, versus looking to other cultures where there are tons of ways to not eat meat and change the grammar of the plate, the ways these ingredients come together, because you’re not expecting a fourth or a third or a half to be meat.

Thinking about these questions of gender and race and colonial, imperial histories of these views of tofu, of tempeh—this was also a white colonial power way of looking down on these other cultures and othering them in part through food that didn’t come from animals. It’s complicated, to unbraid all of that and to think about different ways to eat.

When we think about the energy consumption of cities and neighborhoods and vehicles, of homes and big buildings, there are so many other things that we can change, too. I wrote a really short piece about an SNL spoof commercial for these GE Big Boy appliances [Sarah laughs] where the washing machine was six feet tall and has a 70-pound door that a woman could never use, and it also runs on gasoline, so it has a F-minus energy rating.

We have studies of folks talking to men about doing any of these more green behaviors—having a more energy-efficient smaller car, using less water in the shower, all these things—and they’re resistant to those changes. So it’s not just meat. When we look more broadly, we can see these other spaces in which that resistance takes place. But I think meat is so powerful as a signifier, as a part of our diet, that it’s where debates center.

We’re in this moment where consumers are still trying to escape advertising even though it’s everywhere. It still has this power to offer up these options of who we can be, and so when we’re in such tight boxes, we’re literally doing harm to people as they move through the world.

For individual readers and consumers, I hope they have the experience I did when I was 20 and first doing this research, where you have the critical tools to identify the messages and resist them if they are harmful to you.

Do you think The Dude was impacted by the pandemic? And did the experience of COVID align a lot with your research? Did it challenge it in any way?

The narrative I track in the conclusion is what happens after 2016, because I think we hit a different moment where The Dude is sort of destabilized. How can we continue to market man drinks and man food in a moment where we’re having legislative, cultural, and social conversations about transgender visibility and rights? That conversation is not done. There is still so much work left to be done, when we look at the kinds of laws³ that are still being passed all over this country that are inhabiting the rights of transgender folks.

³Citing data from the Human Rights Campaign, ABC News reports that as of March 12, 2021, there have been 82 bills introduced that seek to limit the rights of trans people, including trans youth, since the start of this current legislation session.

Marketing and advertising has always considered themselves the most modern of people. They want to be leading the way forward. For ad firms and their clients, the brands and the products they’re supporting, there was this moment of social responsibility. Some of the brands that I write about in the book dropped a focus about gender. Some regressed and got even more conventional and frustrating.

I actually got the book back to do final copy edits in April of 2020. The pandemic had started, and I didn’t know long it was going to last. There was no way that I could have known at that point the huge effects the pandemic was going to have on work and on laborers. With the Great Recession, which is the time period that I’m looking at in the book, the cultural effects of two years of economic mayhem lasted for so much longer in people’s lives.

At that time, job loss was more pronounced among men, so this idea of a he-cession was part of the context that The Dude emerged from. He actually came from a cultural moment and then was manipulated and transformed by industry and marketing messages. But this recession has been a she-cession. It’s affected women, and particularly women of color, in the service sector, so it played out really differently.

The book was able to respond a little bit to the context of the pandemic, but I think personally, maybe the saddest thing was to have it come out in a pandemic. A project you’ve worked on for a decade: You dream of book launches and book talks and all these fun things, and it’s all Zoom. [Emily laughs.] That was definitely a bummer, although it has come with some amazing things. To get to have conversations with folks in different cities and different countries? Maybe that wouldn’t have happened without us pivoting so quickly to virtual events and a digital world.

Left: Emily walking her dog, Raven; Right: Writing outside in the sunshine

I would like the arguments in my book to become irrelevant. I want there to be no more binary gender target marketing happening in food media. I don’t want to see the gender dynamics of power that I write about in this book replicated. But every day, it feels like I have a friend send me something like “Oh my gosh, this made me think of your book, look at this.”

I’m happy, selfishly, as an author, when that happens, but as a person who wants to see a future for food media that’s full of more justice and more joy, I’m really disappointed that I’m basically just gathering evidence where I could make a second edition if I wanted to. This isn’t over.

For the marketing, food media sort of worlds, I do hope that this is a wake-up call, that this is the damage we’re doing when we lay gender over food and flavor and ingredients and ways of eating, appetites, our bodies, the way we move through the world.

We’re in this moment where consumers are still trying to escape advertising even though it’s everywhere. It still has this power to offer up these options of who we can be, and so when we’re in such tight boxes, we’re literally doing harm to people as they move through the world.

For individual readers and consumers, I hope they have the experience I did when I was 20 and first doing this research, where you have the critical tools to identify the messages and resist them if they are harmful to you, whether it's about how you think about your gender identity or how you think about your body or how you move through the world. You recognize what’s going on, and you can be a part of the push forward to ask these industries to do better and to do more.

I just want that on a plaque somewhere. [Emily laughs.] Genuinely, I mean that.

I think work like yours pulls to the surface all these different threads that are tied to these marionettes that we all operate under. It makes those things visible. We live in a world where so much is made purposefully invisible; so much is kept from us. And in so much being kept from us, I think we’re also kept from ourselves, and from there, each other.

I always like to end with a fun question, so: Jane Fonda! I was reading your blog and found your post on her workout tapes and how teachers can apply that to online teaching. If you could host the wonderful Jane Fonda for a dinner party, what would you make for her, and why?

You know, I’m such a jerk and a bad food person, because I don’t want her for a dinner party, I want to work out with her! [Sarah laughs.] And then I want to have a really refreshing seltzer beverage with wonderful herbs added to it and talk about her incredible life and activism.

The way that I come to food and food culture is thinking about anxieties and contractions and paradoxes. Her own journey with her body is one of a story a little bit like mine. Having an eating disorder, doing ballet and then getting injured, she finds the workout, but maybe ends up in kind of an exercise bulimic state. You can love exercise and do too much of it; that was my life for a long time, too.

She stayed so very very thin and trim her whole life, I wonder if she got to that place of being able to really enjoy food and not feel like she had to restrict or restrain around it. I don't know how happy and easy a dinner party would be. I started the book remembering my grandmother who would cook and do all the effort for Thanksgiving with my mom, but then when we sat down to eat, she’d have a Lean Cuisine meal. I’d seen that, and I’d seen this very very thin body as a part of my family; then, trying to be a ballet dancer in a naturally muscular body, I knew the lengths I had to go to fit that model.

I think I can do the Jane Fonda workout now because it’s set in the 80s, because the leotards and the hair and the bows [Sarah laughs] are all so fantastical that it’s like in a different reality. In that way, I don’t feel the oppression of those very very thin bodies. Instead, it can be a space with fun music and fun choreography, and it’s so much fun to move your body. And it’s a good workout! You work all your muscles and you stretch and you sweat, and it’s just really wonderful.

But someone responded to that [post] saying that this was also a really destructive tape for some people, in the kind of bodily ideals it was putting forward, so I think the conversation with Jane Fonda would be really interesting, but it might bring some of that up.

I think for me, that connection between food and our bodies is part of what I always hold onto. Some food folks just study the food. I’m really interested in what happens when we eat it and it becomes part of us and our relationships with our bodies and ourselves.

Sign up for Currantly, our newsletter delivering original food stories and news analysis, with surprise treats of freshly curated recipes and product drops. Think of it as your monthlyish digest to deepen your stance on food issues and be creatively inspired.

Bios

Sarah Cooke is a freelance writer and reporter based in Washington, D.C. Her reporting, which explores the intersection of food, culture, and power, has appeared in DCist, Eater DC, and Washington City Paper.

Emily Contois researches food, the body, health, and identities in contemporary U.S. media and popular culture. She is a professor at The University of Tulsa, the author of Diners, Dudes & Diets: How Gender and Power Collide in Food Media and Culture, and co-editor of a forthcoming volume, #FoodInstagram: Identity, Influence, and Negotiation. She's written for Jezebel and NBC News, been on podcasts like Gastropod, Extra Spicy, BBC Food Chain, and Food Psych, and appeared on CBS This Morning, BBC Ideas, and Ugly Delicious on Netflix.

Sign up for Currantly, our monthlyish newsletter delivering original food stories and news analysis, plus fresh curations of recipes and product drops.