PROFILE

Lucas Sin Redefines the Chef

WORDS & PRODUCTION BY VICKY GU

GRAPHICS BY CLARE LAGOMARSINO

IMAGES & VIDEOS COURTESY OF LUCAS SIN

APRIL 1, 2021

Image: Sepehr Mokhtarzadeh

Hong Kong-raised and New York City-based, Lucas Sin's on a mission to immortalize Chinese culinary heritage. As Chef of Junzi Kitchen and Nice Day Chinese in New York, NY and New Haven, CT, he leads a vanguard of socially engaged chefs catering to the digital diner—while creating new language for the food stories as yet to be told.

On your phone or short on time? Read the mobile version here.

"LISTENING. LEARNING. PLOTTING. PLANNING. STRATEGIZING. MOBILIZING." This is not the introduction you'd expect from a self professed shy boy. Lucas Sin's Instagram bio reads like an activist meets consultant meets landscape architect, barring the first word to cast out confusion: CHEF.

As it suggests, Sin doesn't identify with the old guard of often bombastic chefs singularly focused on perfecting a World's 50 Best restaurant or expanding their dine-in empire. At 27, he and his generation came to age in a chaotically globalized and now mid-pandemic world. His food is made to order for the needs of the postmodern diner: culturally curious people who are very online, all the time, and hungry not just for a firecracker chicken bowl but for explosive change. (Exhibit A: his Chinese fast casual restaurants Junzi Kitchen and Nice Day first started in liberal arts college hotspots across New Haven, Greenwich Village, and Morningside Heights.)

An Rong Xu

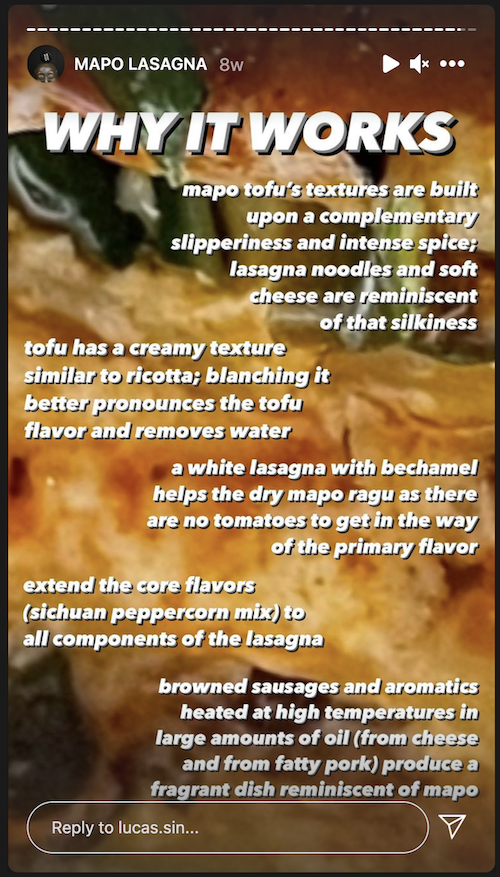

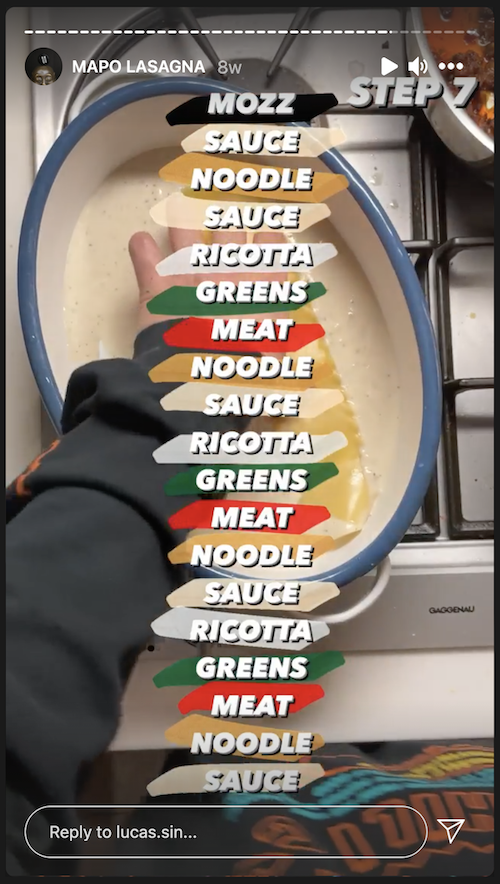

"I mean, anybody should be able to cook Chinese food. Not only in the Yan Can Cook kind of way, but also in the way that Chinese food can be infectious into any type of cuisine. I'm obsessed with this idea that people can be making Puerto Rican plantains or Cambodian noodles and that an understanding of Chinese culinary history will make those more delicious. Because that's how really good cooking has left its legacy throughout the history of the world. If you think about French cooking, the reason why bechamel is in American lasagna is because it's an approachable and easy sauce to use, and it's just been left behind in a way that is applicable to multiple cuisines. I think that type of cultural and culinary confluence is really interesting to see."

A past cognitive science major, Sin knows that getting people to change the way they cook starts with changing the way they think. And that in a hyper-digital, homebound era, what we think is increasingly shaped by mass media and its spiraling tendrils—wherein he commissions his digital horcruxes on mission to immortalize Chinese cuisine.

—

I almost thought he wouldn't show for our first Zoom call. He apologized for the scheduling delay leading up. It'd been a busy of couple weeks. He’d just cooked for grassroots initiative #EnoughIsEnough, raising awareness for hate crimes against Asian Americans. Shortly after, The Infatuation backed him to livestream a recipe demo from their splashy new cha chaan teng zine, for which he called in actor-comedian Jimmy O. Yang as pupil-accomplice. The next week, he retrofitted a Junzi Kitchen location into an ad hoc manufactory to churn out luxe chili oil sets developed with The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

But he does indeed log in, sporting a white crew cut tee, a clothy brown cardigan, and black over-ear headphones in front of a white wall. It feels startlingly gentle, for someone who's comfortable with fifty thousand strangers watching him emphatically noodle slurp over a fluorescent lit stovetop.

I shouldn’t be surprised it feels anticlimactic, given we live in an age where anyone can arrange their digital narrative at its most alluring angles. Instagram fortune favors the visually and verbally and socially gifted, like Sin. Yet even thoughtful edits can’t compete with the compression machine that is social media, trapping our nuanced layers of humanity in transit through the interwebs.

"A lot of people are like, the dude speaks English, so you must be from California, you know that type of thing?," Sin notes. I laugh, because people have also guessed me—an English-speaking black-haired, fair-skinned, stubby-nosed person—to be from California.

Sin is from neither the boba-rich Valley of San Gabriel nor the boba-barren plains of Iowa. He's from Hong Kong, a special administrative region of China ceded from the Qing dynasty to Britain for 99 years (and returned in 1997). It's the native land of famed cultural exports Jackie Chan and the chicken rice and noodle dish that inspired the world's first Michelin-starred street food cart. Hong Kongers own the conceit of growing up in one of the most cosmopolitan cities in the world, anchored by the richness of intuiting this is their land without needing to sing it in school.

Coming to America for college, Sin acknowledges "the privilege of not having to wrestle with your identity, one of the benefits of growing up as a majority in your country. I didn't really have to think about it until within 16 hours of [travel time] becoming a minority in the United States. The advantage is that I don't need to go through the often arduous and labor intensive hoops of explaining my identity, so that my opinion can be heard in a very identity focused social media space...I’m not Asian American. And it makes talking about Asian food easier."

Sin isn’t just “not Asian American.” He’s also not just Chinese in the broad vernacular interpretation. More specifically, he's Cantonese, part of an emerging generation of transnational Asians, a concept posited by writer E. Tammy Kim.

He didn't have a Fresh Off the Boat tiger mom or workaholic dad who was too busy working or dealing with quotidian discrimination at work to be anything but nonplussed about his kid's "passions." He had a developmental therapist mother and co-conspirator father who encouraged him to open his first restaurant in an abandoned newspaper factory in high school, paving the way for his next culinary pop up in a college basement. Sin grew up 7,061 miles away from Asian America, a strange galaxy where its inhabitants spent high school internalizing and bemoaning their stinky lunchboxes until adulthood. His world sounds freeing, beautiful, at least for a few fleeting moments.

"On the other hand, there are absolutely topics and context in which making my own identity and background clear is important. But it's also difficult because we don't have literature as a precedent framework to think about our own identity, because we are relatively new. And I would also bring attention to Chinese people in America, specifically because of how tumultuous that immigration pattern has been. Like, within a short period of time, people are not here to make beef and broccoli anymore. People are suddenly here to go to Pratt. And so it becomes harder to reflect because there isn't that much language around to analyze this, because it's still ongoing history."

—

The most famous Cantonese of Sin's precedent-forging generation might be Jackson Wang, a kpop-trained singer-rapper (and coincidentally, the same age as Sin). His latest bop nods to listeners across the oceans, featuring retro synthesizer-forward pop of the 80s and a self-directed music video inspired by 90s Hong Kong cinema.

Sin is a polymath chef just as Wang is a multi-hyphenate, globally aware entertainer. On his personal Instagram alone—and extended to mass publications like Bon Appetit and Vice's Munchies—he takes on the roles of full stack writer/publisher, stylist/photographer, and scientist/historian, woven together in reverberating nerd energy. He explores the structural similarities of mapo tofu and lasagna with exuberant chutzpah. He explains how German colonialism in the city of Qingdao yielded Tsingtao, the light lager he uses to cook stir fried spicy clams. He's thoughtful with his words but not precious (there's six instances of "fucking" as an adjective in the transcript of our conversation). Sin's stories reflect deep knowledge but also a hidden source of inspiration, thanks to his American education at Yale: literary figures like Joan Didion, David Foster Wallace, and David Sedaris. (Specific to food, he references Michael W. Twitty and Burkhard Bilger.)

"In college I spent a lot of time in the English department, and whether you're writing a literary analysis or a short story or poem, you have to justify the things that you say. You have to be as aware of what you're saying as how you're saying it.

While we were young, my parents also emphasized that the most important thing is language. For them, for that generation, it was being fluent in English and Chinese. In my college studies, I think I expanded that understanding of language to not just be the language of the country, but language as a mode of communication."

Sin wrote his undergraduate thesis on mental time travel, deconstructing the magic that happens in the prefrontal cortex when you think about eating a sandwich in the past, present, and future. Storytelling—"the code and language by which your mind operates"—was the best metaphor he found to describe the process. Instagram—today’s de facto storytelling platform—just happened to provide a digital sandbox to refine on his theories in real life.

Now at over fifty thousand followers after just a year of professional activity, Sin struggles to describe his posting process (a good sign). Three times, he mentions his “allergy to social media” while bristling at "content creator" as a label. He doesn't look at the camera when he speaks, and it feels especially apt now. He's looking all over the four corners of the screen for language that has yet to be created on the social dilemma. As opposed to when he speaks on food—the words spilling out like an overflowing bowl of broth—even talking about social media induces labor.

He didn't always have to think that much. Before his current iteration of slickly formatted stories intended for mass consumption, he "was never hungry for followers and never really posted, I just like shit posted and stuff for my friends." Fast forward to now, when I liken his posts to bite-sized creative nonfiction.

"I mean, that's the best way to think about it. Part of the reason why I don't post so often is because there's not much to post about, but whenever I do, I have a process of writing it on my computer first with a keyboard. And then let it sit for a day and edit it. Like five, six sentences, but you just want to make sure that the sentences are tight.

It’s an exercise of translating what you're thinking into English. It's arduous, it takes time and it's a learned skill." I ask him where he learned it. He reminisces on his favorite class in college:

🎧 Listen: Lucas on Literary Translation

"As for editing the story or the narrative, number one, make sure it's clear and eloquent and understandable and easily digestible. That's a question of color and font and angles and how you film and at what time of the day you're filming."

What Sin describes is an answer to the human impulse to create beauty out of chaos. It's the deeply involved process of a poet crafting phrases, videographer setting a scene, and prop artist making sure the chopsticks are placed just right. In an algorithmic and API-fueled world, it's an ongoing defiance against unthinking, prosaic language and flat lay feeds ridden with “omg drooling, recipe pls!!”

Naturally—"Yeah, I don't want to make it seem like I'm not crazy about Instagram, but I'm a little nervous about social media in general, in terms of its pressures, and how it fits into your regular life. There's something about the constancy and the rhythm of social media that I find can be oppressive and can actually diminish from the quality of the content or the quality of the things that you're doing."

It's not just him. The allergy to social media runs on a societal level, and popping Benadryls won’t quell it. Instead, we feast off stimulants of intuitive UX design, shipped by technological beasts concealing their true nature behind cute, bouncy animations. We expect our public figures to be full stack producers and marketers, detracting attention and care from their full time jobs. We pepper them with questions, praises, and snide remarks to which they'll answer with authority and eloquence because we have constructed two choices: fade into irrelevance or feed our codependency. Social media has become proof of life while simultaneously draining it.

So what's the antidote? For Sin, it’s his collective. The community, as they say. Or, friends.

"I can point to other people and be like, hey, check on my buddies. [Reporters] are like, hey, can you give me a scallion pancake recipe? I'm like, no, that's not me. That's my buddy, Eric [Sze]. Or, hey, can you talk about Jing Fong closing and unions? And I'm like, hey, that's not me. Look at Chinatown Artists Association, or talk to this reporter over at The New York Times."

"We have this collective sound that I think is very, very exciting. Before the pandemic, I would tell people that this is the best time to make Asian food in the US because your heroes are your peers. There's so much diversity and power in this collective community of chef voices. It's not about the singular rockstars anymore. And when you want to see a movement and a change in the way people eat and the way people cook, it comes from a wave of multiple people doing something, right. And as an insider, as a chef, you can see what those tiny ripples can be like. Like a Taiwanese certified dish of minced meat and garlic chives popping up on menus everywhere, or Malaysian coffee versus Vietnamese coffee being differentiated. It's exciting to be a part of.

When I first came to New York and met with a PR agency, they were like, what's your deal? What do you want to sell people? Lucas Sin is a chef that represents what? They really needed a singular answer. They're like, do you want to become the Yan Can Cook? The Chinese cooking guy? I was like, no, it doesn't feel really right. And now more than ever, I feel like you don't need to define yourself. I can just be this guy, as long as I’m part of a cool collective of people that can influence culture and push it in the right direction."

Still, followers and reporters flock to him, whether a source for research-backed recipes to bolster the amateur culinary oeuvre, or as a traffic director to point them in the right direction. Even if he’s good at it, it adds to his seemingly interminable quota of invisible emotional labor.

"I'm not primarily a content creator. My biggest responsibility at this point is still my restaurants and my job and the people that I work with. Especially this year, that's the most difficult thing to do, get your restaurant to survive and continue to exist. And from a small business perspective, it's about keeping your costs in check and finding a way to have a healthy amount of sales. And those sorts of things often aren't that exciting to talk about in an interview. But that's the reality."

"If we had another hour, I would love to imagine a future in which chefs don't exist. Where restaurants as a business are distinct from chefs as voices. There's a lot of difficult ethics there, because from an economic standpoint, the risks and the rewards that exist within the food system right now are so poorly balanced. And the wrong people have the wrong type of risks on their shoulders without any chance for reward. And with whatever angle you address it through, whether that angle is gender, or race or class, or cuisine, it's always going to be inequitable because the risk and rewards are all over the place."

If precedent tells us anything, perhaps that goes hand in hand with a future in which influencers also don't exist. Where chefs aren't inflamed by their followings, and press managers can pitch new concepts instead of repackaged catchphrases. Where editors aren't afraid to publish recipes with titles in different languages, because readers aren't hesitant to click on foreign words. Where diners and home cooks co-develop relationships with the people serving and teaching them.

What Sin is imagining is a world of renewed language, where we think before we type. Where public figures aren't unduly responsible for the audience or platform they have. Where we're responsible for ourselves to do the damn work.

At a Munchies shoot featuring Hong Kong style french toast

“Smoking” some beef chili on Sin's first trip in the woods this year

I bring up his related Google search terms—currently, "golden rice recipe" and "sweet potato"—to frame the dreaded legacy question: what would his ideal search terms be?

He brings his hands up and massages his cheeks in exasperation. "Um, I don't know. [Pauses.] If I die, and my search terms are fried rice and sweet potato forever...

It's fine if the collection of search terms around my name are discrete and specific, like fried rice or sweet potato. But if as a collective, you can look at all those words and feel like this person has a library, or at least a collection of recipes that point towards a certain philosophy of cooking—which is up to the editors and the publishing houses of any cookbooks I write in the future to determine—but something along the lines of simplicity and elegance and inclusivity—it's a good starting point. Could be worse. You know? Like, I'll tell you what would be worse, if it was like, oh my god, I should be careful here. I'm on the record.

I was thinking if it was soup dumpling, it would just be a little bit too neat. Like this is a Chinese Chinese Chinese thing, that I can't apply to any other thing. My whole thing with golden fried rice is that yeah, it's kind of a Chinese recipe, but I put ranch in the mine, I put like buffalo hot sauce and Chinese XO sauce—”

I interrupt to gush over Molly Yeh's All the Alliums Fried Rice, featuring Sriracha mayo sauce, a rotating favorite recipe between me and my last roommate from the Southwest.

"Exactly, and like that's the whole thing with the sweet potato too, like you can dress it up. That was developed with Kia Damon for a Chinese Creole dinner, it was supposed to be like sweet potato pie."

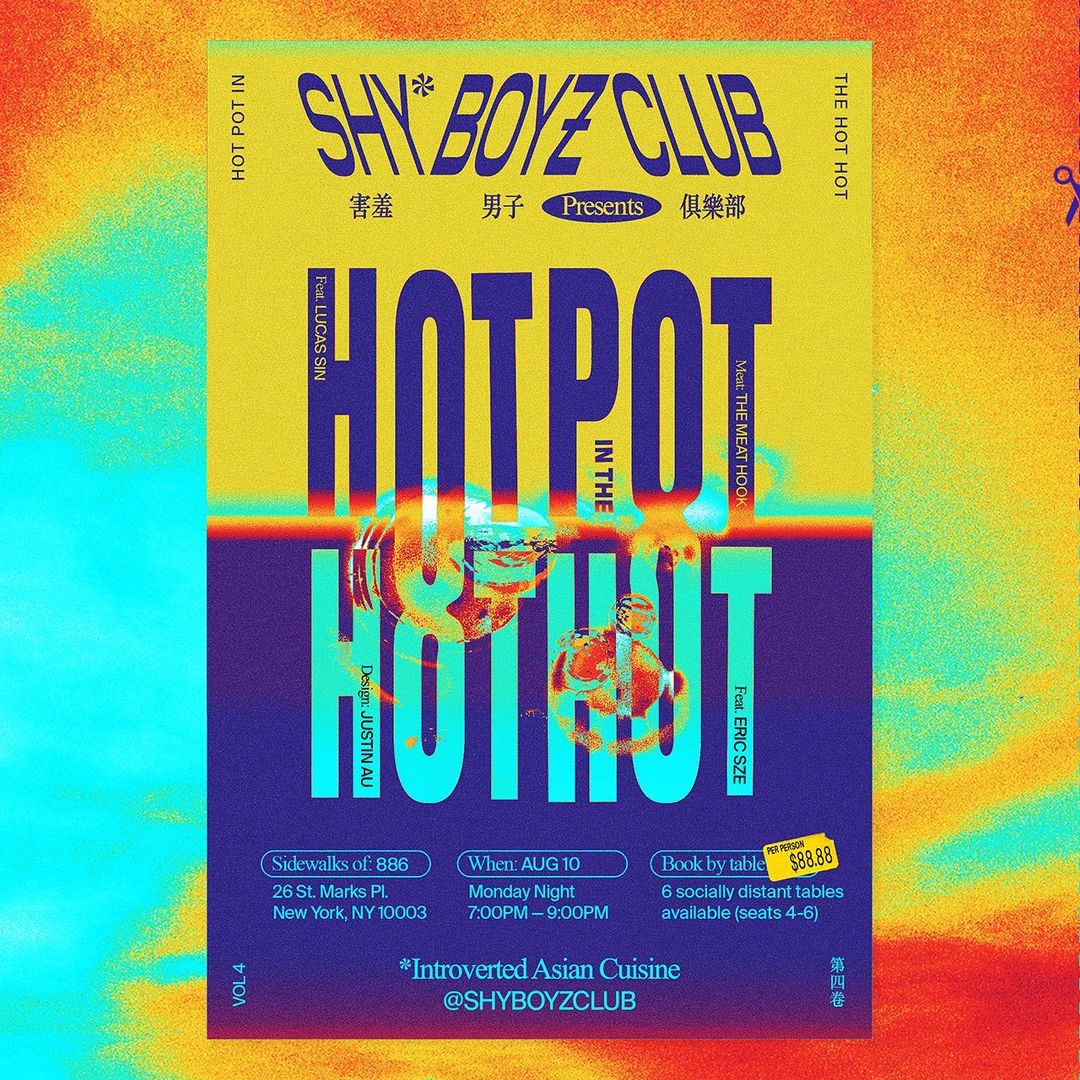

Design: Justin Au

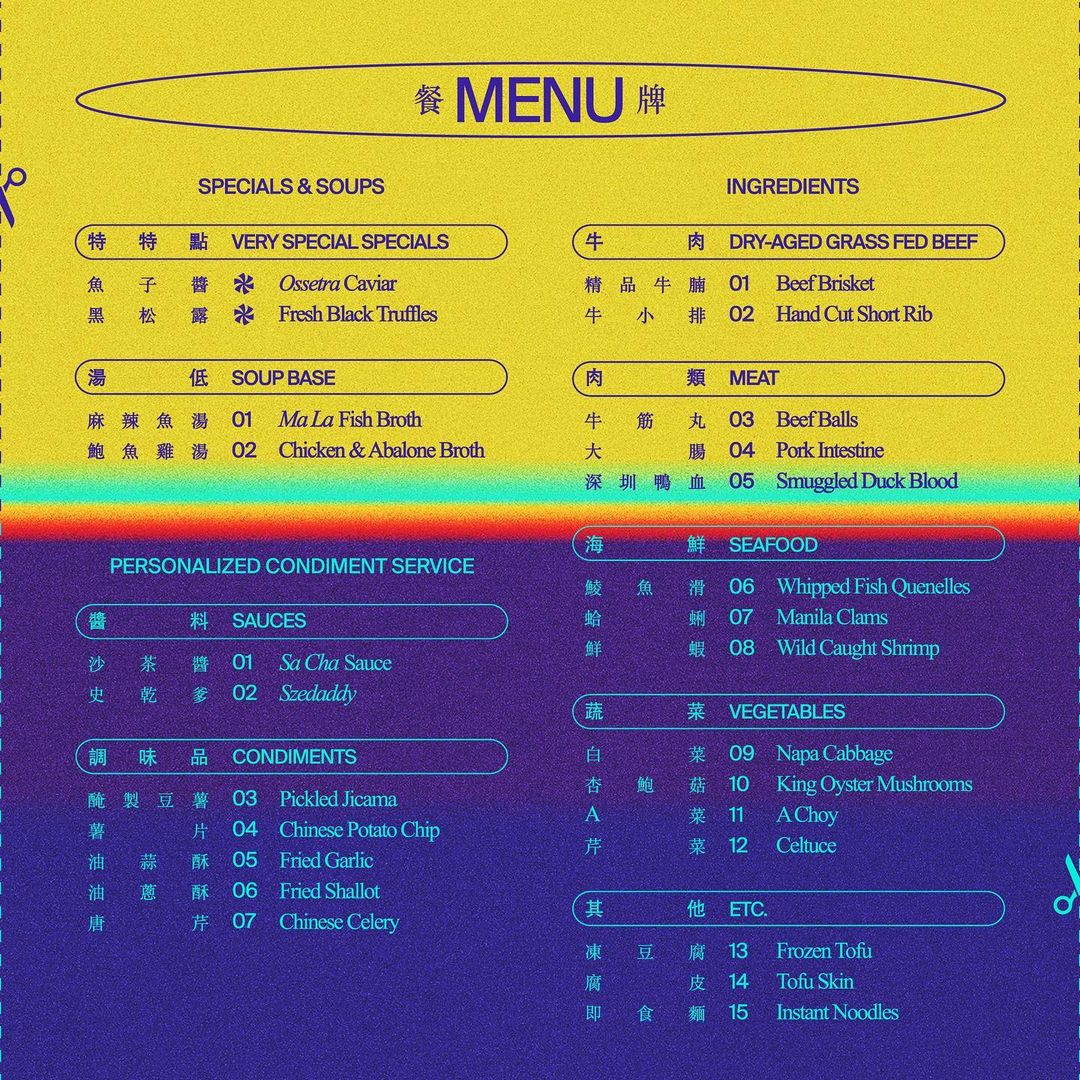

Sin’s legacy takes intriguing shape in SHY*BOYZCLUB, his nostalgic and rebellious pet project created with chef Eric Sze and designer Justin Au. Unconstrained by financial viability, it’s a dinner party where Sin, Sze, & friends "flex [their] culinary skills and stupid ideas and just have fun." The product is “introverted Asian cuisine” that doesn’t pay heed to authenticity—flavors that are concurrently bastardized and sublimated. Unabashed in both design and menu, SHY*BOYZCLUB reads as pure celebration.

It’s necessary spaces like these that complicate the interplay between our private and public perceptions, rendering back in 3D our caricatures flattened by digital translation. As noted by a friend who cooked with Sin in college: "I don't see Lucas as shy; he's one of the most charismatic people I know."

But we live in America the capital of capitalism, where passion projects don’t pay rent or feed teams or disrupt industries, at least until a middle class of creators emerges. I was surprised by references to the "right" career slinking through our conversations, buoyed by ironic jokes on the iridescent gleams of consulting industry bubbles.

Sin remains clear-eyed about the path ahead, career hesitancies notwithstanding. Supercharged on the spicy energy of a thousand chili oils, he’s on track to encode new memory of Chinese-ish food and Chinese-ish cooking—for everyone, unironically. He's humble but not modest, conscious of the power of his words in charting equitable relationships between food, people, and industry.

Yet no matter how successful his mission, his Google search terms aren't up to him. They're also up to you.

Sign up for Currantly, our newsletter delivering original food stories and news analysis, with surprise treats of freshly curated recipes and product drops. Think of it as a monthlyish digest to deepen your stance on food issues and be creatively inspired.

Sign up for Currantly, our monthlyish newsletter delivering original food stories and news analysis, plus fresh curations of recipes and product drops.