INTERVIEW

Photographer Clay Williams Cares A Lot About Process—and People

WORDS BY SARAH COOKE

GRAPHICS BY CLARE LAGOMARSINO

PHOTOS COURTESY OF CLAY WILLIAMS

APRIL 15, 2021

Clay Williams began photographing food and drink for blogs, newspapers and magazines in 2006. In the years since, he's hung off the back of food trucks in Paris, sweat it out in tight kitchens with Michelin-starred chefs and wandered through cattle farms with a team of butchers. He photographs assignments for The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, The James Beard Foundation and Imbibe Magazine among others.

Clay is also the co-founder of Black Food Folks, a platform for Black professionals working in food, food service and food media. The group has provided a space for members to meet, network, collaborate and tell their stories.

+++

So much of food is about movement—chopping produce, quickly tossing together a pasta sauce so that it doesn’t clump. Capturing that liveness in photographs is no easy thing, but Clay Williams makes it look effortless. His work breathes with life.

This conversation, which was held on March 22, 2021, has been edited and condensed for clarity.

On your phone or short on time? Read the mobile version here.

I want to start with an old bio you have on Serious Eats. You call yourself “Blogger, Photographer, Geek.” We’ll talk about the photography, but let’s start with the geek. Tell me about that.

I came up with that tagline back in the days when I was a full-time IT worker. My day job was professional geek, and then I started blogging, I started photographing. These days, I don’t really blog at all anymore. Occasionally, I’ll do some writing.

My wife will tell you that I’m not the tech support spouse anymore. [Both laugh.] She’s like, “Did you run this update?” I’m like, “No, I’m three versions back cause it works.” [Sarah laughs.] I regularly start swearing at Apple or Google or whatever, because I don’t care about the tech anymore. I just want to be able to do my job. [Clay laughs.]

I do sort of geek out to food; that’s a part of who I am. Connecting to or thinking about food, whether it’s when I’m cooking, what we’re gonna to eat, where I want to go so that we can get food or whatever. Who am I supporting? Who I am connecting with? Who am I talking to on Instagram, or who am I following? Whose recipes am I trying to hone? That sort of thing.

I guess the geek still applies. It’s just not quite at the forefront anymore.

It’s not the full Geek Squad. [Both laugh.]

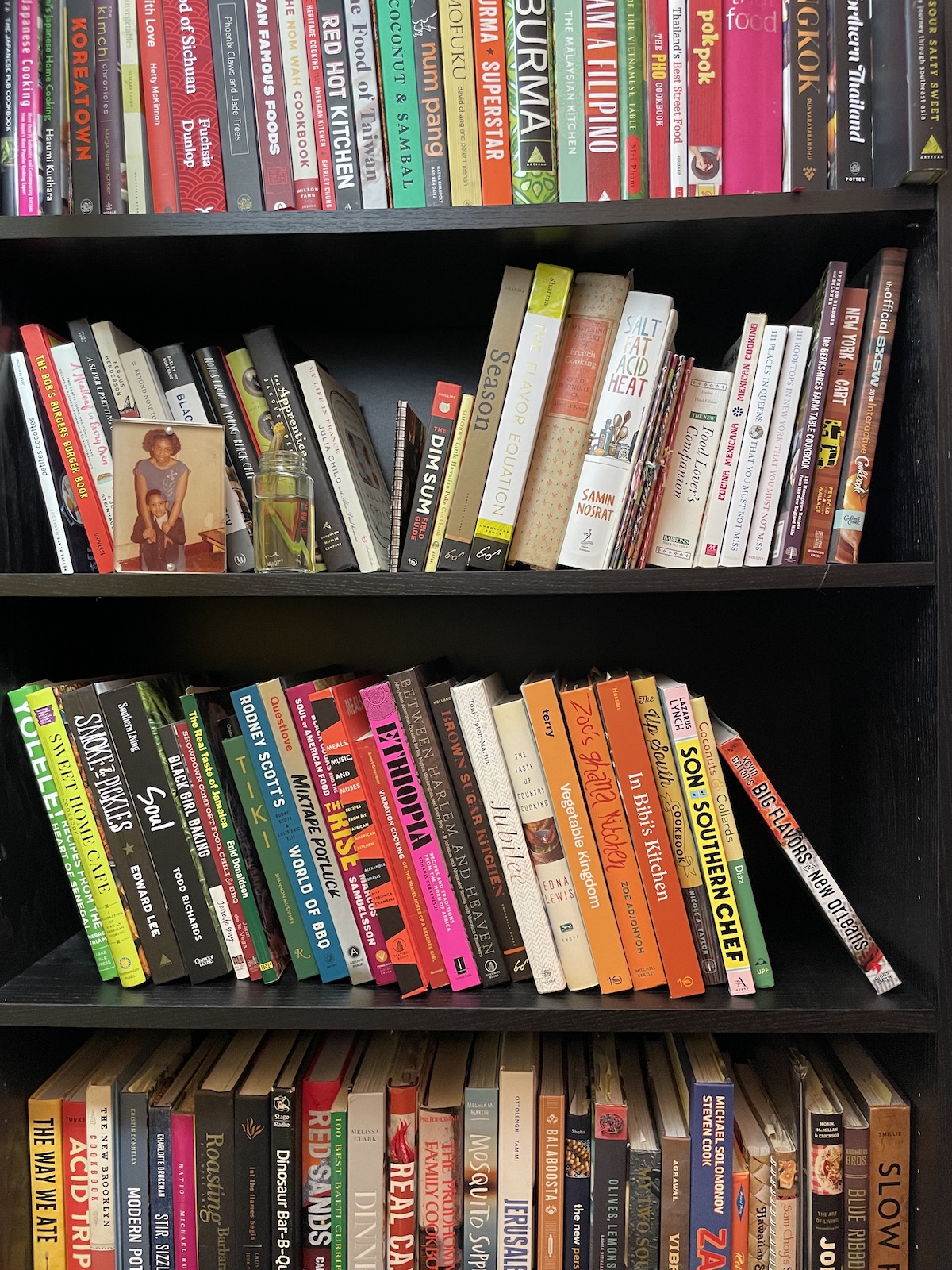

Clay's brand new bookshelf, "which is more exciting to me than it should be. Besides just adding some better organization to my backdrop for many Zooms and Instagram Lives, so I feel like it’s become a part of the window into my life the world sees."

I heard you talk on a podcast about taking black and white photography in high school. At the time, what drew you to photography? And now, what parts of yourself does it help you connect with?

I don’t know what it was that drew me to it initially, but the photography classes were just for the high schoolers, so as soon as I got to high school, I was like, “That’s definitely one of the classes I’m taking.” [Sarah laughs.] In addition to capturing moments and all of that, there was also just the time in the darkroom, the chemical smell, going through the images, developing the film.

There was a commitment to each shot that’s a lot different from the way things are now [with digital]. And I’m not romantic about or pining for those days professionally, I totally couldn’t do it. I mean, I play with film these days, but I don’t see it as something that I could do as my main work most of the time.

Sorry, I’m totally going off the rails with this. I don’t know if this is at all what you’re looking for. [Clay laughs.]

In high school I actually took a few photography classes. We had this tiny closet space where we would shake the canisters of film, and every time I shook a canister, I would be like, “Oh God, this is where I mess up.” [Clay laughs.]

What parts of yourself does photography help you connect with, or is it really more of a tool to connect with the world at large? Or both?

You know, it’s a funny thing, because as much as photography was a big part of my high school experience, when I went to college, I sort of figured, I’m not doing that anymore.

When I was working in IT, one of the things I had to do was evaluate digital cameras—just point-and-shoot, not professional style. One of the magazines that our company worked with wanted to replace the polaroids that they used for the fashion closet. I had to evaluate a couple models, and it de facto became a camera I had with me all the time. (This was the early 2000s, so we were years away from cameras in phones.) As my quote-un-quote evaluation [both laugh], I used it all the time.

This was the beauty of digital: it became less about, “I have to get this one shot,” and more just unselfconsciously getting moments. It didn’t have to be the decisive moment¹. It just has to be capturing the time.

¹In 1952, photographer Henri Cartier-Bresson published Images à la sauvette, a book of his work; in English, the title was translated as "The Decisive Moment."

Cartier-Bresson also co-founded Magnum, a global collective of photographers. Today, he is considered one of the most significant photographers of the 20th century. He died in 2004.

I was in my mid-to-late 20s when Brooklyn the brand started [Sarah laughs], when Marlow and Sons, Diner, and Brooklyn Kitchen opened. Everyone started talking about farm-to-table; there were butchering classes, everyone was making artisanal this-and-that.

For all the sort of hipster extremism there might have been, there was this creativity at that moment that was just everywhere. Having a camera in my pocket that I could use to capture all that was what really drew me into it: the events, the openings, the parties, the food.

Meredith Leigh (@mereleighfood) skinning and prepping a recently slaughtered lamb at a Chefs Boot Camp in the summer of 2019

One of the first things that I kept coming back to was butchering, because it brought together my personal curiosity about food and cooking, and also my photographic curiosity about capturing the moment when, say, an animal becomes a piece of meat, or when that piece of meat becomes food, something that we are used to seeing on the plate.

I would be a regular at certain restaurants or butcher restaurants. I’d get to talking to people, and I’d ask them if I could come into the kitchen or go behind the counter and shoot them at work. Sometimes, they said yes. [Both laugh.] I would blog or post about it somewhere, and people started seeing my work, and they would ask if I could do it for them.

I think my first blog-y photography thing was probably somewhere between 2005 and 2007. It became an excuse to go to more of that stuff and to not just go as like, “Oh, it’ll be fun,” but to go and really be a part of it and observe it.

What attracted me was being able to really see the things that are happening. Sometimes that meant literal access, and sometimes that meant just by being there in the role of observer, I got to be in it but not all the way in it.

I would be shooting music and I’d get backstage or stage access sometimes—which was nice, but also by giving me the focus on work, it meant that I was able to both be in it but also separate from it. Does that make sense?

That makes a lot of sense. You’re not the one who is going all out on the drum kit, but you’re seeing somebody do that. You are the conduit for people to get as close to the feeling or the experience as they can without being in it.

Sometimes I think more so than being in it, because the other people are there to experience whatever it is in a particular way. They’re there to eat the food, they’re there to eat with friends, they’re there to lose out their shit to the music. [Sarah laughs.] They’re not seeing close up what’s happening in the kitchen; they’re not getting the flame up on the grill. They’re not necessarily seeing the sweat on the line cook’s face.

It’s not just capturing that moment, but it’s also sharing something that they wouldn’t necessarily be seeing themselves.

So much of my ideal food media is making transparent the process of how anything becomes food and the labor that’s involved. In my ideal world, having a sense of that would change how an individual relates to the food that’s in front of them. Knowing its history, knowing the people involved. Having an appreciation for the line cook who is sweating profusely in front of this dish.

Honestly, process is one of the things that I stopped saying so much, in part because it used to be the thing that I would say every time. That’s pretty much exactly it: that process, that transformation, that’s what drew me to all of this, and that’s the thing that keeps me coming back. The people are part of that process, too; the people are the instigator of that process.

I’m thinking about a butcher who is still a friend of mine. I started doing this when he had just gotten his training, and I was still doing this all just for fun. When I think about this, I still think about it in relation to him. His hands, his face, when’s he getting in there trying to separate the bone from the meat.

I don’t think of myself as an artist so much as somebody who really captures moments and people: the emotion, the feeling, all of that. That is part of what process is to me. It’s about those hands, it’s about those faces, it’s about the action.

I think there’s an art to being able to see people, really see them, maybe sometimes in a way that they can’t see themselves. I actually think that can be one of the most generous gifts that you can give somebody. I see that in your work.

You were talking about the moment of transformation for process, and I’m curious how you apply that ethos to when you’re photographing people for portraits.

Portraits are interesting. To me, the most important part of portraiture, as I do it, is that I want the person to be comfortable.

I have done a decent amount of event photography work, and a lot of times I find that those sort of unknown moments, those candid moments, are the ones that are a best capture of that person: when they’re not posing, when they’re not presenting something that they think is what you’re looking for.

Obviously, if you’re doing a portrait session, they know you’re there. [Both laugh.] I try to engage with them as much as possible, so that they are less self-conscious and are more comfortable with me. I may take five times as many shots because I want them to get used to the sound of the shutter and the action that’s happening. I want them in motion, so I have to work around that.

That’s what I do in kitchens, and that’s what I do with portraiture as much as I can: try to get people at ease doing the things that they’re doing. A lot of the time, someone will hire me for a headshot shoot, and I’ll have a couple of places that I think are comfortable or will photograph well, but I’ll also ask them if there are areas that they’re interested in. And we’ll walk and we’ll try a couple places. I’ll say, “What do you think about this? How about over here?”

By letting them be a part of that creative process, it feels more like we’re just trying some stuff out. I think it reduces the pressure of feeling like, “I have to do something, I have to pose a certain way, I need to be this way or that way.”

It’s more like, we’ve got some options, we’re gonna try a few things. And that’s what I like to capture. I want people laughing, I want people engaged. I don’t want the pose they think I'm looking for. I want them to be presented as they are.

I don’t think of myself as an artist so much as somebody who really captures moments and people: the emotion, the feeling, all of that. That is part of what process is to me. It’s about those hands, it’s about those faces, it’s about the action.

I hear such a groundedness in you. Is that something you’ve always had?

I guess so. I’ve never really thought about it. But sometimes people are surprised I’m from New York [Sarah laughs], because I’m kind of more relaxed. I’m not as tense, necessarily, as people think of New Yorkers being.

I mean, I’m just as impatient as anyone else; like, get out of the way, I’m trying to get somewhere. [Both laugh.] I stress as much as anybody else, but I look at it as, “Okay, well, the stress isn’t helping me, it’s just something that’s there.” I’ve had to figure out how to keep that calm, certainly, over the last couple of years, but it is something that I guess is sort of my personality.

I definitely have my freakout moments, but I try to be as aware of it as possible, so I don’t spiral. It’s not something that’s going to help me do whatever I need to do better. [Both laugh.] It's like, okay, I get it, this might be a total catastrophe, I understand. I’m not gonna spend too much time thinking about the ways it can be a catastrophe. I’m pretty sure I know how this might ruin my career or might be an entire embarrassment, right; I don’t need to spend too much time on this. [Clay laughs.]

I’m pretty cognizant of it. Once we have that out of the way—yes, this might all go to hell—that lets me figure out how to get through it in a way that hopefully means it won’t.

I don’t know what makes me think that more than anything or anyone else, but it is useful.

I am someone who is very much prone to spiraling, and my therapist always calls me on it.

I’m hearing an ethos that makes a lot of sense about why you co-founded Black Food Folks: really wanting people to feel seen, and feel seen for their full expansiveness, their authenticity and who they are.

At the Brown & Balanced Launch Party, you said, “We have to build things that are not dependent on other folks, so that when inevitably, some other thing happens...everything we built shouldn’t fall apart. We shouldn’t be so dependent on that current attention that we can’t stand on our own.” What is it like to help lead that community? How has it changed since 2019?

On the practical level, it was just that I kept having conversations with people where the common thread was always: “How can we help each other?” Invariably, I would talk to somebody, and their story would resonate with something I’d heard from somebody else in one way or another.

Colleen Vincent and I met through our friend Nicole A. Taylor, who is brilliant and wonderful and has historically been the great connector for a lot of folks in the Black food community in New York. I found myself doing that more often; Colleen’s the same. We were like, “Well, we could introduce all these people individually over however many months or years, or we could just get some folks together; and so, why don’t we just get some folks together?”

My very reasonable idea is that it would just be 20, 30 people in the back of a bar somewhere. Colleen thinks bigger. This was a little bit of a freakout moment for me, when the emails started going out and we started spreading the word, and suddenly, our list went from 30 people to 100 people. [Both laugh.]

We rolled with it, but at the same time, it was like, “Oh, this is something everybody wants and needs.” It felt like it came when we needed it, both in terms of seeing so many people that we’d only run into at events or getting together for drinks, but then also meeting new people who I’d heard of or had seen before or seen their work. Seeing people that are doing very similarly inspired work who didn’t know each other but should absolutely know each other.

There was this conviviality, this warmth, from the event that was amazing. And then, stepping back and looking and realizing that we had 100-odd Black folks who work in food in one room. Every other event I go to, there might be that many people, and being paid to work there, I’m one of two or three Black people in the room, and hearing organizers—very nice people—saying they just don’t know Black food folks [both laugh] or they’re not sure who to talk to.

It’s like, if you put any effort at all into this, you would be able to have a room like this. This was not some giant organized thing, this was me and Colleen emailing a couple people who then brought a couple people who then brought a couple other people. It was something we threw together in two weeks.

From there, it was like, well this is obviously necessary. For the first year and a half, or year and change, I put together a monthly newsletter that I used to call the internal memo for the Black Food Community. It was celebrations: this person got this published, this person got a book deal, that person wrote this story. This restaurant’s hiring, or this person’s won an award.

Last year during lockdown, I was bouncing off the walls. I never quite thought of myself as an extrovert exactly, but I realized how much I needed connection last year, and so seeing what people were doing on Instagram Live, Colleen and I talked about hosting our own gatherings and having these conversations, having something worthwhile.

We’re still having these conversations and hosting. Now, we’re launching a podcast, and we’re doing an editorial partnership with Resy. All these things are an extension of the original mission, which is bringing folks together and creating space where people can share stories.

At the end of the day, what we need is more voices, and more people doing it, and so that’s it for me. We’re doing this so that more people might do it, and more people can get their opinions out. To go back to what I said during the Brown and Balanced thing: I do think it’s essential that we are not dependent on other people’s attention. I think I may even have said then that when I say that people’s attention will move somewhere else, it’s not a condemnation of them.

The world is crazy; there’s always some new crazy thing, right, and it’s not unreasonable to say that yes, people are going to be moving focus from the immediate issue to a new immediate issue. That’s fine, but that shouldn’t mean that there’s no place for us to exist.

Did you ever see that movie Pleasantville²?

²It's rumored that Pleasantview, a neighborhood in The Sims 2, is named after this movie.

No!

These teenagers somehow get transported into one of those 1950 sitcom towns. When everyone is gone, the mother just sits at the table. She had no agency: unless she was doing something for somebody else, there was nothing for her to do. She disappeared if she wasn’t connecting to somebody else. And we need to not be that.

That’s sort of the idea for us: when other people don’t see us, we’re still here. And we still are doing work, and we still are telling our stories or we’re still making our food. And that means something.

We’re not here to be a part of somebody else’s story. This is the thing our pop culture has told us for ages, that women and Black folks and gay folks and Asians and whoever are there as a point in somebody else’s story. The sassy friend or sidekick.

The idea is that we don’t need that. So when I say that we need to build things, it’s so that when the next trend or whatever kicks off, we’re able to exist, we’re able to have our own space that celebrates us outside of February, outside of Black History Month and Juneteenth. We exist, and we’re doing interesting things all the time.

Was that like 20 minutes? I have no idea. [Clay laughs.]

In a way, it’s like building a house, and having rooms for, in this case, every Black person working in food media. They have their studio, they have their space for a celebration of their work, for they are. If you’ve got a strong house, that house lasts.

Clay's office for the day recently in Philadelphia, shooting dishes for Irwin’s by Chef Michael Vincent Ferreri in the Bok Building, a former high school turned artisan space

I always like to end with a fun question. What is the thing you are most looking to shooting post-pandemic?

Probably something travel-related. Throughout 2019, I travelled with the James Beard Foundation to photograph their Chefs Boot Camp series, which is a great program. They bring in people who work in government and lobbying and explain the cogs of government and how chefs and restaurant owners can engage with their communities locally and nationally to effect change.

The RESTAURANTS Act took a year [to pass]. Everything that I saw people doing was part of that process that I'd seen taught as a part of that project. As the chef, you are potentially a small business owner, you’re a leader in your community, you are a boss, you are a member of your larger community, and you have priorities and values and things that you are interested in.

During the program, they’d go around the room and say, raise your hands if you’ve had your mayor come into your restaurant, your senator, your governor, a presidential candidate or president. If those people think that coming to your place is a part of connecting to the community, then you should be able to tell them what this community needs.

It’s an important project, but it also brings these folks out to a farm, or we end up staying on the farm and tour the farm. As a part of understanding the value of the products and where things come from, there’s also an animal slaughter that they learn about the animal, what they grow, and then they go back and cook this collaborative dinner using that meat.

People form connections with each other in a way, because they're working on this thing together. It’s always pretty meaningful to me. There’s so much about it that I think is important, but also, there’s so much about it that I enjoy: connecting with folks over an extended period of time. That’s on my list of what I'd love to be shooting again when this is all over.

Sign up for Currantly, our newsletter delivering original food stories and news analysis, with surprise treats of freshly curated recipes and product drops. Think of it as your monthlyish digest to deepen your stance on food issues and be creatively inspired.

Sarah Cooke is a freelance writer is a freelance writer and reporter based in Washington, D.C. Her reporting, which explores the intersection of food, culture, and power, has appeared in DCist, Eater DC, and Washington City Paper.

Sign up for Currantly, our monthlyish newsletter delivering original food stories and news analysis, plus fresh curations of recipes and product drops.