INTERVIEW

Liana Aghajanian on the Alchemy of Writing

WORDS BY SARAH COOKE

IMAGES COURTESY OF LIANA AGHAJANIAN

GRAPHIC BY CLARE LAGOMARSINO

MARCH 25, 2021

Liana Aghajanian is a journalist who specializes in and is passionate about long form, narrative story telling and international reporting. Her reporting has appeared in the New York Times, The Guardian, BBC, Foreign Policy, Pacific Standard, Marie Claire, Los Angeles Magazine, Al Jazeera America, Newsweek, Los Angeles Times, LA Weekly, The Atlantic, Mental Floss, Roads & Kingdoms, Brownbook, Narratively and several other national and international publications. She is currently documenting the Armenian experience in America through food with her project, Dining in Diaspora, where she’s tracing the intersection of cuisine and agriculture with genocide, immigration, identity and more.

This interview, held on February 12, 2021, has been condensed and edited for clarity.

On your phone or short on time? Read the mobile friendly version here.

Sarah: You call journalism your “excuse to get to know the world.” Did you always want to be a journalist? Were there other paths that also offered those appealing excuses?

I think there are paths that offer that excuse, but I gravitated towards journalism pretty early on. By the time I was 13, I was on the newspaper staff at school, and I produced my high school yearbook all four years of high school. [Liana laughs.]

I even did something really nerdy in my senior year: I went to something called yearbook camp, where schools from a 20 mile radius get together and plan out their yearbook and engage in competitions together. It was the dorkiest thing I’ve probably done. Given that I enjoyed every minute of it, I think it was pretty solid that I was going to pursue writing and journalism as a career. It just always seemed to be the most comforting, but also challenging, in a good way, direction that I took.

I have two follow ups there. One: Why yearbook? And two: You said challenging. I’m curious about that as well. How was it challenging? Or what was it challenging?

Yearbook because that’s just what was available at my high school, and I loved the idea of getting to know every single student. I guess even at that point, it was just an excuse to get to know people at my high school.

In terms of the challenges, I think writing is a very challenging thing, and I’m comforted when other writers talk about that. I don’t find it something that necessarily comes easy, but the challenges are ones that I feel I can eventually overcome, and I’m better for them.

Writing in general, for anybody who does it and is thoughtful about it, is really hard. It’s often not seen that way, because everyone can technically write, but in order to write well and to write for the right audience and piece together a story—it’s not an easy feat.

I love the process of having written. Like, I love the end, but getting there is not always an easy process. [Sarah and Liana laugh.] Which I’m sure a lot of writers can relate to.

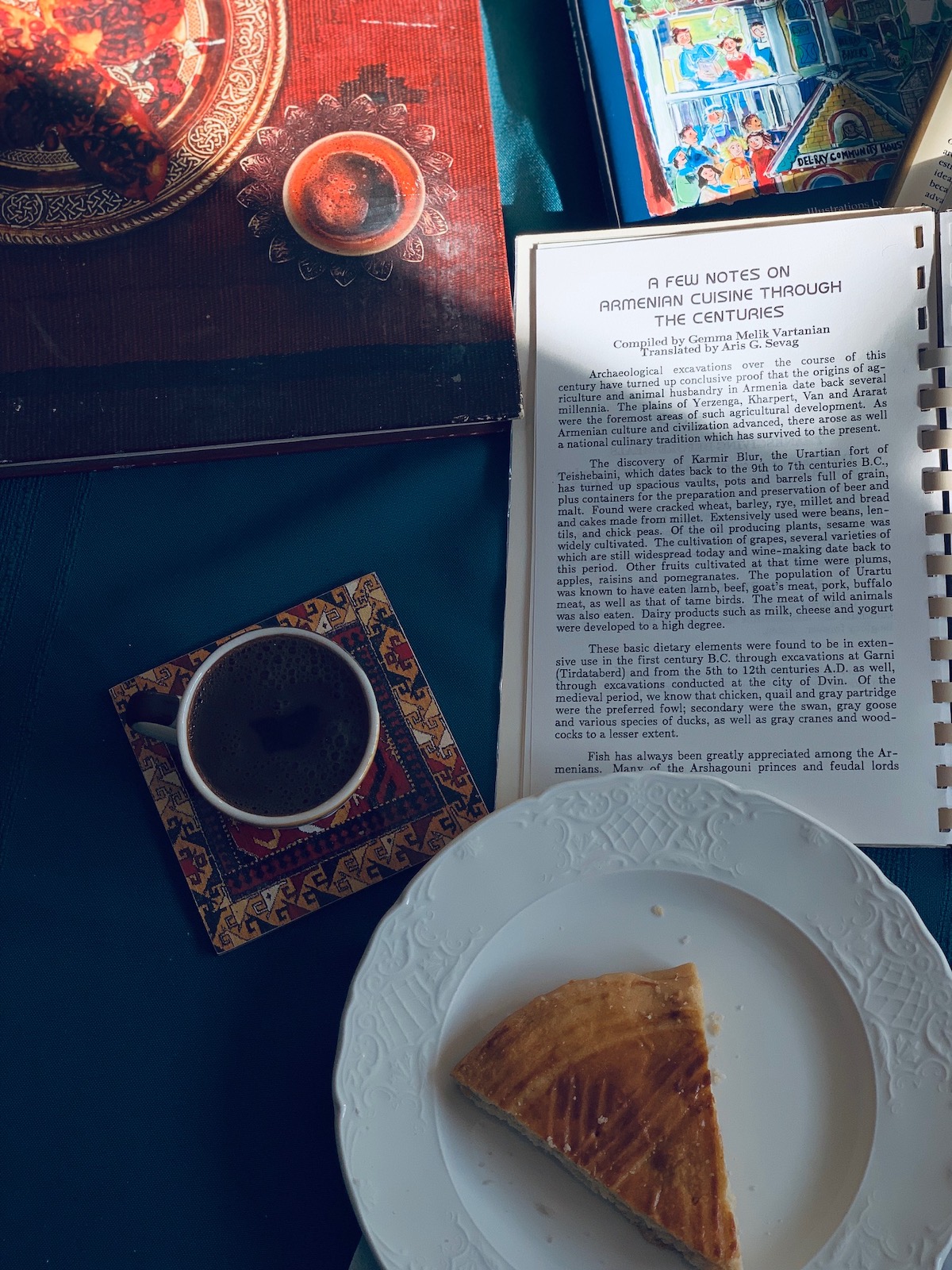

Marking the first time the sun really came out during lockdown last year in Detroit

Liana working on her ongoing Armenian culinary project with coffee and gata, an Armenian sweet pastry

I’m thinking now about that interview you did with Nieman Storyboard, where you talked about the perception that journalism isn’t actually “creative” writing. You said: “It’s the truth, but writing about the truth doesn’t mean you don’t have to put skill into translating something so someone will actually read your work.” What is that process of translation like for you?

It feels like a puzzle that has parts that don’t fit together at first. I think the talent in doing journalism is being able to take all of those pieces and to arrange them in a way or add color to in a way that is readable.

I can’t remember who said this to me, but it’s always stayed with me: “The easiest thing in the world to do is to stop reading.” I think the art of journalism means being able to get someone to the end of a story.

There are so many elements to it. There’s the pre-recording aspect of trying to figure out if it’s a story worth telling; there’s being able to contact the right people and getting them on board to actually interview with you; there’s going through documents; there’s fact finding. There’s data, there’s analytics, and then there’s the actual field reporting that you have to do—and then, being able to take all of those elements and put them in a way in which someone is going to get something out of it, whether it’s just pure information or some profound feeling.

It’s a process, and I don’t think people understand that process. I wish we were more transparent about it, because if we were, then I think that would do journalism a service for the public, for people to know how journalism is made. I think that would lead to less doubts about the purpose it serves and the truth it can provide, which is obviously a huge challenge these days in the US.

How do you show that work in a way that emphasizes the importance of that work? It’s a challenge for any profession, but I think especially for journalism, where it’s both taken so much for granted here in the United States, and then also, taken so much for a beating at the punching bag.

Was food always a part of your journalism?

I gravitated towards the odd food piece here and there, because who doesn’t want to write about food? It’s a great topic to delve into. But I was balancing that out with other topics that I loved to cover or story ideas that didn’t involve food.

It started to increase in the last four or five years when I moved to Detroit. I think that was really the catalyst of when I did more serious food writing—although I don’t really consider myself a food writer, just somebody who writes about food. Being in Detroit solidified that for me, and that was because of the project [Dining in Diaspora] I took on to document this legacy of immigrant food as it related to my background in the US.

If you take a look at the writing I did up until Detroit, and even in Detroit, it’s kind of all over the place, in the sense that I never had a beat, I was just pursuing ideas that I really was passionate about. When I started writing more about food, it was the first time that I focused in on a topic that stayed with me for longer than just one piece.

Making Kharpert Kufta with the Women's Guild of St. John Armenian Church in Southfield, Michigan

Mulberries handpicked from a tree near Liana's backyard in Detroit. They were later turned into jam.

Is it fair to say that your approach to food—as a vehicle through which people preserve and sustain their stories, their cultures, their histories—is a guiding ethic for you? Do you feel that writing about food has helped you clarify or deepen your commitments?

I think so, because when I started to do that kind of food writing, I was not necessarily pitching any of it quickly, or pitching any of it at all. For me, it was a passion project. I think that freedom made me more dedicated to that focus, because it was something I was just doing for the pure love of doing it, and for what I felt was important to do.

I think anytime you’re writing, whether you’re freelance or a staff writer, it’s always good to have that little project on the side that you really like. It also functioned for me as a form of sanity amongst the political situation that took place in 2015 and 2016, and it was something that I went towards for a source of comfort.

I think that’s really important with writing and how challenging that career and lifestyle can be: to focus in on a little project that you love. The more you do it, the more you find out what you really like and define your focuses.

I know that if there’s rice in my pantry, things are going to be okay. [Liana laughs.] It kind of feels like that; it’s like a little pocket or place you can go, or a thing that you have, if it’s physical. Like, “If I can focus on that, and that can be the thing that threads me through all of this shit, then I’ve got that.” It’s one thing, but it’s one thing.

I love that rice analogy. That’s really, really good.

Rice is this kind of food which can be turned into other things, and so it feels like a grounding you can stand on. It’s a similar feeling for me with rice, because a lot of the dishes that I eat with my family involve rice.

I see how my mom takes that and makes different things from it, and I think the writing is the same way, too. Whether the rice or that little project, you can kind of have that to stand on. Even if everything else is falling apart or not working out. [Sarah laughs.]

Cooking is alchemy. I think that’s actually why a lot of people who love writing and the process of storytelling seem to gravitate towards food in some way, either as people who love food or write about it. There’s some magic in food that also seems to find itself in writing.

Unlike the writing, which of course the writing can also be tangible, the food is tangible. You can feel it with your hands. It provides the other sense of comfort, and maybe a bit of control.

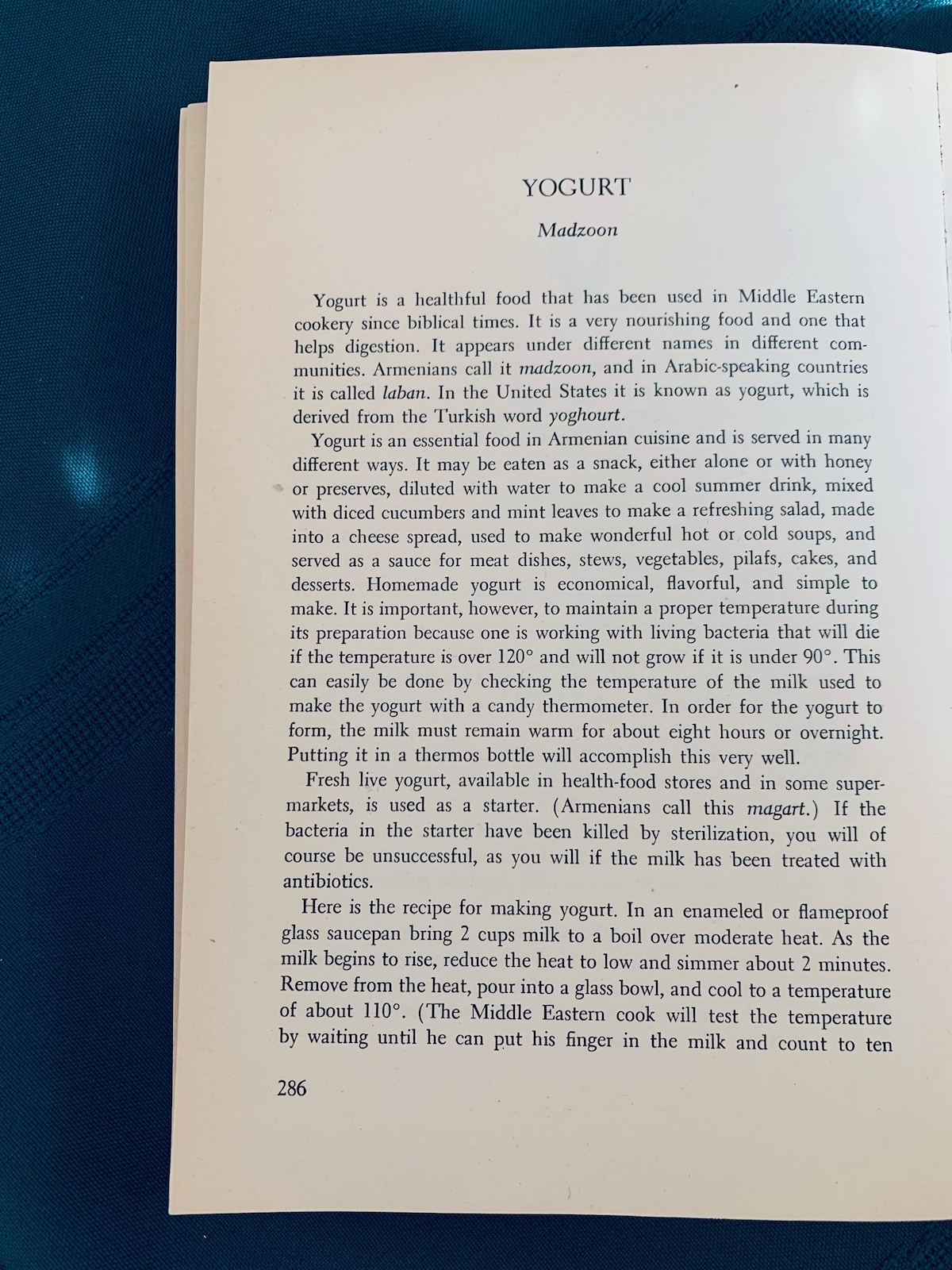

Yogurt Liana made using a very ancient culture from an Armenian family she's writing about

Has COVID and the travel restrictions impacted the work you’re doing with Dining in Diaspora? I’m curious to learn where it is as a project right now—where you want to take it, if COVID is giving you any downtime or more time to think through what you see as its future.

COVID has impacted it, because the whole premise of it was meant to be a thing where I did travel and meet different communities of Armenian descent across the US, and obviously that has been put on hold. But I have managed to do some work, pre-interviews or even virtual interviews.

In terms of what it gave me, it gave me more time to focus. It made me figure out what direction I wanted to take the project. Right now, it’s in a proposal phase, because I’m hoping to turn it into a book; the proposal is out there in the world, and I’m going to see what’s going to happen with that.

Basically, this is the only kind of thing that I have worked on that feels like it has that sort of longevity, that the stories are connected to each other and that I feel like I’m the right person to tell those stories, and that I want to pursue it. I’m ready to be in it for the long haul. [Liana laughs.]

There’s not a lot of work that I’ve done that I felt that way about; usually, you work really hard on the project, and then you move on to something else. But this project feels like it’s going to be with me for a really long time, and hopefully it will be in the shape that I want, which is an actual published book.

I’ve read several essays, including the quince jam one. Each essay feels like its own poem, and when you put them together, they’re this constellation. It’s just beautiful, and I can see it being such an incredible book.

Thank you, I really appreciate you saying that, and actually reading it! [Liana laughs.] I’m always surprised to hear that people are reading those pieces, because when I start writing them, I never think they’re gonna resonate that deeply.

I think because the topic and the history that comes along with it is so complex, it feels like there is a lot of material there and a lot to still discover, so the whole process for me is in some ways a discovery, too. I’m learning along with the stories I’m telling.

It's not that no one has written about Armenian food before, done recipes, or anything like that; it’s just that there’s never been an opportunity to hear those stories next to each other, to show that richness that you’re referring to. And I think that’s what motivates me to keep adding to it.

Are any members of your family following along? Have they shared with you how it is for them to read the project?

I make my sister read everything. [Liana laughs.]

They’ve helped me sometimes recreate recipes that they weren’t familiar with, because as I mentioned, the Armenian food story is so complex that you get different recipes based on where you grew up. The quince jam, for example: My mom is the one who made it with me. I draw on a lot of her expertise in the kitchen to write some of the essays that are more personal to me, just because if I’m writing about myself, I have to write about the food that I grew up with or that I continue to experience in my own family.

If I’ve written about some issue or some person and the way they make something, they’re very open and receptive to eating it and hearing me talk about it. [Liana laughs.] It’s been great. I think part of it is just a kind of self discovery that Armenians are discovering themselves, too, and each other. That’s been a place where my family has come in.

That’s really lovely. Like a circle starting to create links with other circles.

A sweet bread made by Armenians during Easter using mahleb, which is the ground pit of the St. Lucy's cherry

Wrapped grape leaves flavored with sour plums - a recipe from Liana's mom

In 2016, your writing literally won you a house [through the Write A House residency], it was that good. What was the whole experience like for you, not only applying, but then finding out and moving in?

I think that it was just so odd that I gravitated towards it. I mean, the idea of someone saying, “Oh, if you enter this contest, your prize will be a house.” Like, when do you hear that? Never! [Sarah laughs.] So just the oddballness, that that was on offer, was fascinating.

The other aspect was Detroit as a city, because I had always been intrigued by it, and I had always wanted to visit but had never gotten the chance. And I don’t know how I equated that as winning a house; I don’t know how I made the leap from, “Oh, Detroit seems really interesting, let me enter this contest to win a permanent house there.” [Liana and Sarah laugh.]

Detroit seemed like a place that a lot of people had opinions about, but it was underrated in so many ways, and of course, it has its challenges, but it was a place that I could explore and learn about on my own terms without being influenced by what reputation it had or what people thought of it.

I feel like, still, there’s so much about America that I don’t know at all, and so this was just another excuse to get to understand America a bit better.

The process [for the residency] was you sent in a work that you had previously published, without your name on it, and a series of judges reviewed it. They selected ten finalists, and I was one of the finalists. One of the judges was dream hampton, and I just thought so much of her that if she read something I wrote and decided I could be a finalist, that was good enough for me. By then, I had left the US and gone to Mongolia on a reporting trip, and that’s where I found out that I had won. [Sarah and Liana laugh.]

That must have been a fascinating phone call.

I was sitting in the apartment I had rented, and because there’s a huge time difference, it was 1 or 2AM, and they’re like, “You won the house!” and I’m like, “Oh my God, thanks!” [Sarah laughs.]

Going into it knowing that you’re responsible for this whole house was a lot, but I didn’t think too deeply about it. I think that’s what allowed me to apply, be okay with being selected, and actually going there, because if I had thought too deeply about it, some doubt would have creeped into my mind. But I went into it with an extremely open attitude and that it was going to be an adventure, at the very least, and it did turn out to be one.

So now, do you divide your time between Detroit and LA?

Yeah. Because of the pandemic, instead of flying, I drove back from Detroit to LA at the end of last year, and I’m going to be here for a while. My whole family’s in Los Angeles, so I’m stationed here for a bit until I figure out what I’m doing next.

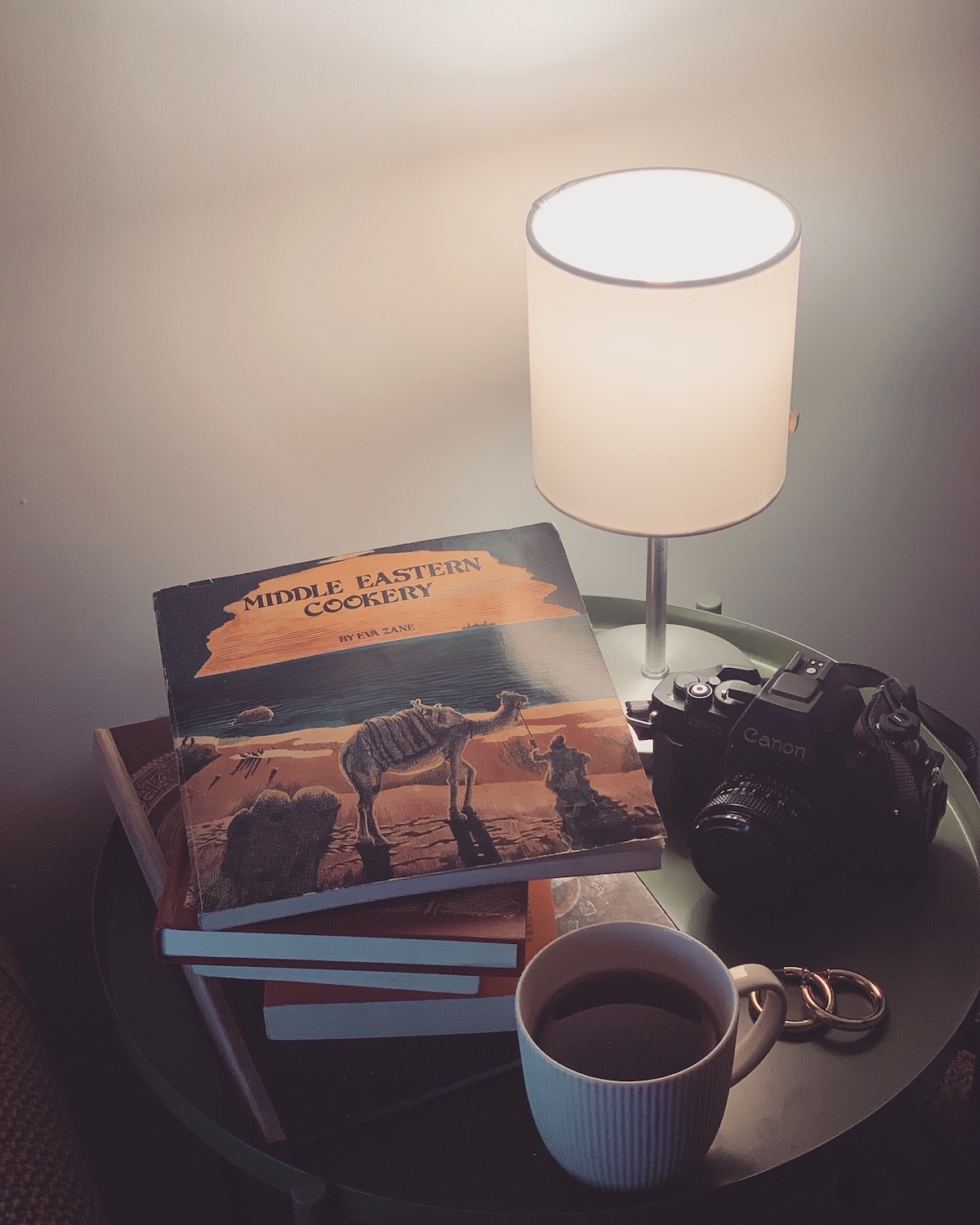

A corner of Liana's writing room, which is filled with various cookbooks on Middle Eastern and Armenian cookery

I really adored that New York Times package you did in 2019 asking “What Makes A Tradition American?” It was a complete road trip, deep-dive immersion into so many different communities across the country. What did you learn from that process? What did you take away from it?

That was part of a package involving four writers and four photographers. We got the route—me and Farah Al Qasimi, who was the photographer—from Detroit, Michigan to New Hampshire. That was about 1,000 miles. [Liana laughs.] We did it in 12 days, I think. We would report and stay in one city every night.

It was an absolute dream assignment. Those don’t come along often. [Sarah and Liana laugh.] It was done a year before the [2020] election, and so I was capturing this moment in time before things could potentially change.

I think I learned that America in general is just changing all the time. It sounds cliché, that the only constant is change, but that’s how it feels. That’s how it felt when we were on the trip, because it was a combination of us going to these cities and learning about the history of the city, but then also interviewing and interacting with people who were doing interesting things in the present day—and they didn’t always necessarily relate to each other.

It was really interesting to me to see America as this kind of ever-evolving place, which obviously happens in every country in the world, but in America, the speed seems to work in a different way. Just finding people and interviewing them that you wouldn’t necessarily expect to be there, or to discover the diversity of a place that is often thought of as not a very diverse place—the piece let us find the hidden pockets of this very big country in which a lot is going on and capture that moment, frozen.

“I can’t remember who said this to me, but it’s always stayed with me: “The easiest thing in the world to do is to stop reading.” I think the art of journalism means being able to get someone to the end of a story.”

I love that kind of reporting. Whenever I read that kind of reporting, it really stays with me. There’s this one documentary by Stephen Fry, which is just him visiting every state in the US. I love that kind of free-form, meandering type of journalism or writing, because it really gives you more depth and the chance to explore more complexity. And if you go to the piece and the way that it’s been presented online, it really takes you on the journey, which I found really cool.

I agree completely with you, that the absence of something you knew definitively for a brief moment in time—that’s the journalism that has such staying power, I think, because it gives you that immediacy of really brief intimacy.

That’s a really great way to describe it. It does feel like that, too.

And everyone we met, when we were with them, it was very intense. We had talked to them on the phone, we’d been texting back and forth, and they were open to us having come and document that small part in their lives. But when you left, it was a fleeting moment; you knew you were never going to meet these people again or see them again, but you managed to capture that small portion of their time.

"Gardening is always like therapy for me," Liana says

I don’t know how to segue into the ending question well, so I’m just going to say it’s the ending question. [Sarah and Liana laugh.] At the 2019 Innovate Armenia festival, you said, “Everyone has a coffee story.” What’s your coffee story? And is it different from your ideal coffee story?

I don’t think I’ve ever thought of my own coffee story. I don’t think I have one coffee story. A lot of the people I talked to at that event did, and that’s what I loved; they had a very specific memory.

My coffee story is just a series of moments in which that particular type of coffee and the ritual that comes along with it was present, ever-present, in my life wherever I went. Whether it was my house, my grandma’s house, my relative’s house, their friend’s house, it was always always there. And whenever I’ve traveled to Armenian homes or I’ve gone overseas to Armenia, that has just been kind of like a museum piece that has always been on the table.

If I think about it deeply, I think my coffee story is that when I was younger, I used to loathe that coffee. I hated it. [Sarah and Liana laugh.] I would tell my parents, “Why are you drinking mud?” It just felt like mud to me, because it was so thick.

But I am now doing that almost everyday, so I have turned into my parents. [Sarah and Liana laugh.] Whether I wanted it to be a part of my life or not, it kind of found me and become part of it. And I’m sure a lot of people who come from either Armenian backgrounds or similar backgrounds, as a kid, there are certain things your parents do and you think, “That’s so weird,” and then you end up just doing the exact same thing.

If I were going to pinpoint a story, that would be it: that I finally turned into my parents with my coffee.

Sign up for Currantly, our newsletter delivering original food stories and news analysis, with surprise treats of freshly curated recipes and product drops. Think of it as your monthlyish digest to deepen your stance on food issues and be creatively inspired.

Sarah Cooke is a freelance writer whose work, including her weekly newsletter Deliciously Intense, Surprisingly Balanced, explores the intersection of food, culture, and power. She lives in Washington, D.C.

Sign up for Currantly, our monthlyish newsletter delivering original food stories and news analysis, plus fresh curations of recipes and product drops.