INTERVIEW

Bettina Makalintal Talks Food Trends and Twitter

WORDS BY SARAH COOKE

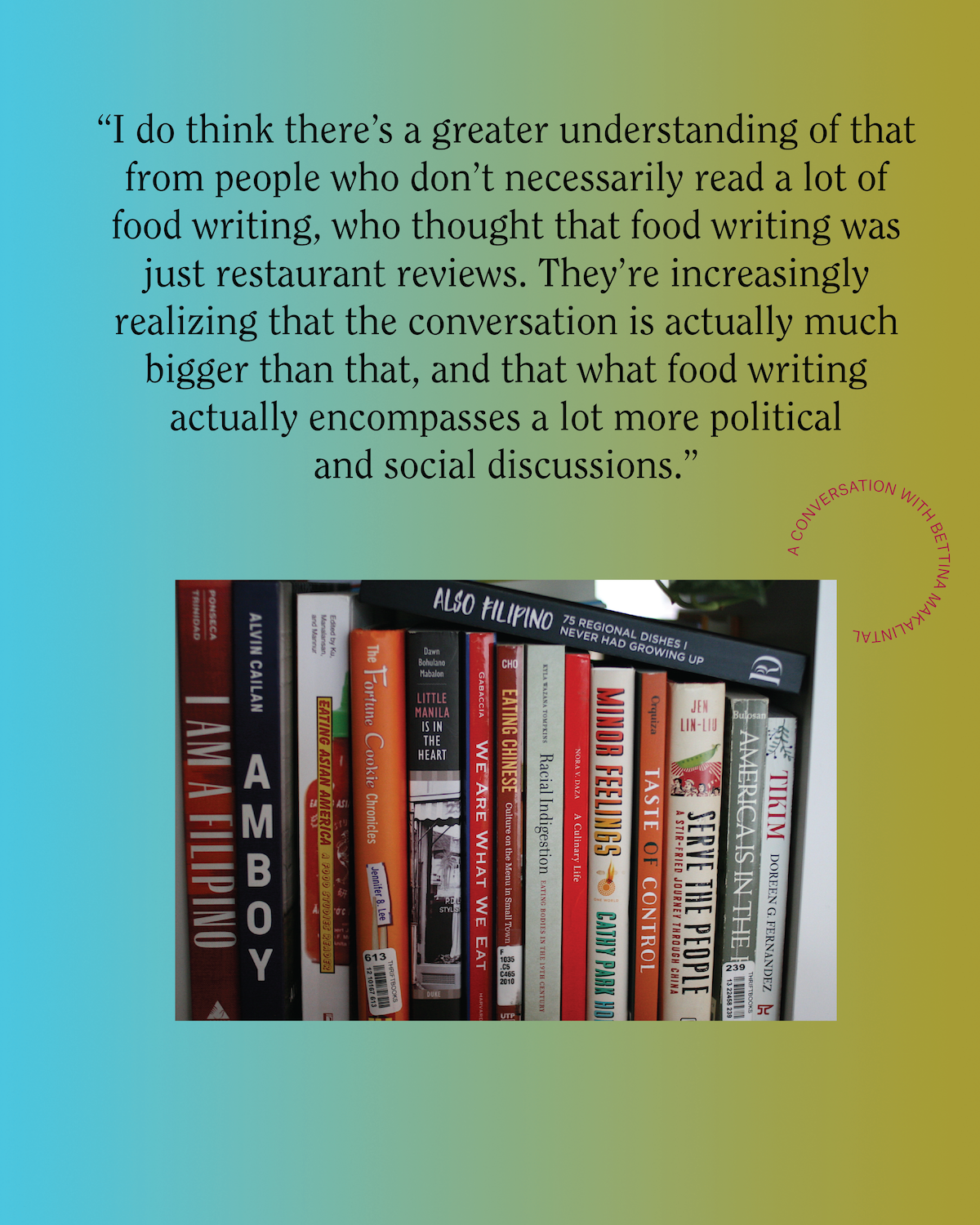

PHOTOS COURTESY OF BETTINA MAKALINTAL

GRAPHICS BY CLARE LAGOMARSINO

FEBRUARY 4, 2021

Bettina Makalintal is a Brooklyn-based staff writer at Vice’s Munchies, where she covers the culture of food. Before joining Vice, she was a freelance writer, ice cream cake decorator, and bike mechanic.

This interview, held on December 4, 2020, has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Sarah: How has COVID affected the type of reporting and writing you do for VICE?

Bettina: I work with a pretty small team, and I’m the only full-time food writer in the culture section. This year, I’ve narrowed my scope a little bit more. I’m not doing very much restaurant coverage, so I’ve focused a little bit more on home cooking and cooking that happens on the internet or distributed mediums.

What got you interested in food and food writing?

I’ve always been a sort of food obsessive. Even as a kid, I would always watch the Food Network and food travel shows, and I would always read my mom’s cookbooks. But for most of my life, I actually thought I was going to go to medical school.

In college, I realized that path was actually not what I liked, and it wasn’t making me happy. On a whim, I took an independent study on food culture and food as a historical object, and that was what made me realize that this is actually a thing I could do.

After I left college and I was figuring out what I do, I worked in food service, and because I was doing that, I was thinking about food constantly and keeping an eye on magazines and meeting people in the food scene. I started freelancing from that point.

I work with a pretty small team, and I’m the only full-time food writer in the culture section. This year, I’ve narrowed my scope a little bit more. I’m not doing very much restaurant coverage, so I’ve focused a little bit more on home cooking and cooking that happens on the internet or distributed mediums.

I saw on your website that you baked cakes, ran an ice cream shop, and then also wrote for a cheese magazine?

In college, I started working at an ice cream shop scooping ice cream, and I was also a barista. Every time I tried to quit and get a new job, I would end up just getting promoted. [Sarah laughs.] So I became the cake decorator and the person managing front of house. After that, I ended up working at a cheese magazine based in Boston.

It’s obvious, it’s a cheese magazine in the title, but what constitutes the work of a cheese magazine?

The one that I worked at was Culture, but there’s also Cheese Connoisseur. Our audience was partially trade people and partially dedicated cheese enthusiasts, so it’s partially what’s the history of certain cheeses and cool projects that people in the cheese industry are doing, and sort of explaining the science of cheese. It was fun. It gave me a lot of very niche knowledge that I don’t use terribly often anymore. [Bettina and Sarah laugh.]

What is some of that niche knowledge, if you feel like you are able to share?

It’s not industry secrets, but for example, it’s like when a cheese has the crunchy crystals inside, that’s tyrosine crystals. Stuff like that but no one actually needs to know. [Bettina laughs.]

Cheese is one of those amazing, weird, absolutely funky wonderful things.

It’s like one of those things where you’re really like, “How did people deduce that this was an edible thing?”

It was fun to dive into that world, because I didn’t know a lot about it when I went into it, then was I like, “Okay, I know way more about cheese than I need to.” [Bettina and Sarah laugh.]

I was reading a lot of your clips at VICE, and what struck me was that some of your work focuses on the psychology and politics of food trends on social media. Does that feel like a fair read?

Yeah, totally. I think that food trends on social media is definitely something I like. And the thing that I like to do is think about it in a deeper way, even if it’s sort of silly on a social media thing.

The perspective I like to take about those things is thinking about them more analytically, to understand what the actual meaning of that trend is, as opposed to just stating that the trend exists.

I think the exciting thing, at least to me, and especially at this point in time, is that a lot of the trends that are happening now are actually just individuals making things happen on social media.

Dalgona coffee was a really good example: how these smaller creators turned it into this huge thing, and then brands got on it.

I was thinking about two recent articles you wrote—one about the rise in Filipino food pop-ups in New York City, the other making a case for more regional approaches, within white food media, to non-white cuisine—and I was wondering about their overlap. With a food trend, there’s The Next Big Thing: a dish, a single recipe, dalgona coffee. But as you wrote, American food media, especially white-led, tends to flatten regional cuisines of non-white countries into one thing, like “Indian food,” when Wikipedia lists nearly 40 different regional cuisines.

Do you see any political possibility in a food trend fighting that monolithic approach? I was trying to figure out if by fact of things being a trend means there’s any hope for more nuance or political possibility, but I would love to get your take on it, since you do bring a much more thoughtful and analytical focus on food trends and how they play into larger culture.

I feel that the way food media has operated is that cultures and cuisines become trends, and I feel like that’s never the way that I want to think about. The way I approach food trends is specific, which is to say, things that are very unique to a particular moment.

To me, what is political is to not consider certain foodways or certain cultural foods as trends. I think that’s what I’m looking at: things that are actually novel, as opposed to discovering something that has existed for a very long time and suddenly calling it a trend.

Yeah. That’s exactly how colonization works.

There’s a lot of media that’s built on predicting trends, and I feel like that’s where you get into trouble, because inevitably, you’re just pulling from things that are unfamiliar to you can suddenly be trendy next year. The way I want to think about trends is just actually observing what is new that people are doing. I think it’s that predictive nature that lends itself to this very colonialist and problematic point of view.

How do you personally define culture?

The way I think about it is that culture is the stuff that people interact with on a daily basis and the things that actually dictate the media you’re consuming or taking part in in your life. I think about food as a cultural product and food is just a space where you can think about a lot of other cultural things.

I feel like I’ve been thinking about this a lot, in terms of being a food writer and what that means based on people’s expectations. I feel like when I’m writing things, sometimes I’m like, “Oh, maybe I should talk about the food more.” I’m not writing stuff that’s explaining what things taste like. I very much think just see food as this niche where you can think about a lot of other things and what they mean for people, and how they affect people’s daily lives.

Totally. I had this long-held notion that in order to be a quote-un-quote food writer, you had to be someone who loved writing paragraphs about how something tastes. And I would just be like, “This is good,” or “This made me happy,” and like, that doesn’t qualify you. [Sarah laughs.]

Do you feel like there’s a greater awareness public awareness of the many nuances of food writing, and that it is anchored in food as a cultural product?

I think that this is a thing that food writers have long known, or the food writers that I pay attention to, have always acknowledged. But I do think there’s a greater understanding of that from people who don’t necessarily read a lot of food writing, who thought that food writing was just restaurant reviews. They’re increasingly realizing that the conversation is actually much bigger than that, and that what food writing actually encompasses a lot more political and social discussions.

A conversation I would love to see within more people in food media is figuring out shared language that provides a better alternative to previous, problematic terms that have been the norm. I feel like a lot of us have moved away from saying “ethnic food,” for example, with good reason, and that’s not a phrase that I use. But I feel like there’s still not a consensus on what the alternative is to that.

Especially as we think about food more globally, I would love for a more cohesive understanding of the words that we use, and I feel like that’s a challenge for me as a writer. Instead of saying “ethnic,” for example, I try to be as specific as I can be. I’ll say “food that’s outside the understanding of white European-influenced Americans.”

I feel like the struggle with writing about this stuff is that I feel like it is helpful to be really precise and to be like, “What we’re talking about is food that is from countries that most white Americans who have European backgrounds aren’t immediately familiar with,” right. But there isn’t a way to simplify that in a way that gets at the same nuance of the statement.

This is a conversation I would love for food media to talk about more: what are the words we’re using, and how we can be in agreement that these are actually moving the conversations forward in the way we want them to.

I feel like the thing that I’ve been touching on in a lot of the pieces that I’ve been writing recently is that generalizations are inherently flawed and will never actually perfectly encompass anything. And I wonder if that’s just part of it—that any word, any singular word or short phrase that we could use, would not fully encompass the right idea.

As writers, there’s a tension between wanting to write as if the better future is already here, and writing in a way to make that possible; but then also acknowledging that future isn’t necessarily here, and you have readers that you want to bring with you.

I think it’s a tension that feels fundamentally irresolvable. On the one hand, there’s the argument that if you aren’t using the new language, you fundamentally don’t get it, so you’re not gonna be part of moving forward. I find that argument to be compelling and convincing, but also potentially self-defeating: There are people who maybe do want to “get it,” and they just don’t have the language that is currently being used.

But if you keep using the lowest common denominator, you’re gonna keep using it, and it’s gonna keep getting calcified as “this is how we talk about this thing.”

Yeah, absolutely. I think that when I write, with the phrases I use, I hope to have the reader understand what I mean, as opposed to leaning on these phrases that are amorphous, like “ethnic.”

I think it is on all of us who are writing to be more specific and more nuanced, and understand that we can pick up the readers who want to think about things that way. That’s always my hope. [Bettina laughs.]

A lot of people feel that you have to write for a specific existing audience, but the way that feels more promising to me, and the way I go into writing things, is writing for a potential audience. People you hope exist, as opposed to placating the people that you know exist.

The idea of things being too niche holds us back so much. I think readers do want things that seem niche; I feel like it’s those specific or seemingly odd stories that resonate with people.

I think we would all do well to understand that we can push the understanding of what we think readers want. I feel like I’ve started to see that as a benefit to how I approach things, as opposed to a hindrance, which was perhaps how I might have seen it in the past.

Thinking about broader political and social discussions always brings me back to place and its role in shaping people. You were born in the Philippines, raised outside Philadelphia, and now live in Brooklyn. How has each place shaped you?

I lived in the Philippines until I was five. I have a lot of formative memories, but I also left there very young, so I think that Pennsylvania really is what shaped me.

I’ve been thinking a lot about how I understood myself as Asian growing up in Pennsylvania, and how a lot of my understanding of my identity was sort of this amalgamation of white American suburban experience of what Asian-ness was. I feel like I have mostly created my identity in spaces where I didn’t have a lot of Filipino community.

I grew up not really taking part in a lot of Filipino culture; it was sort of like whatever Asian-ness I could get in suburban Philadelphia. We went to the Chinese buffet, and we went to the Korean grocery store, and we went out for sushi, but I didn’t really have a Filipino community.

I didn’t really start to unpack what being Filipino meant to me until I was living in Boston during college. That was when I started to connect to more Filipino people and think about Filipino food.

Especially because I’ve lived in New York for two years, and a quarter of that time has been in the pandemic, I would say that my understanding of Filipino-ness has largely happened through the internet. That’s been the site of me finding Filipino community and thinking about food more and learning more about those things.

If the internet—and bear with me, because this is a terrible metaphor—were your home or your apartment, how would it be decorated? What is the internet interior of Bettina?

I actually tweeted yesterday a picture of my saved section on Instagram. I use it as a brain dump, but I also use it to pin a lot of stuff for potential stories. I mean, that would be it: a lot of weird cakes and fun colorful aesthetics, and also just a ton of random food. [Sarah laughs.]

I love your food pictures on Twitter. They’re so great. And I love your commentary; you have a great voice on Twitter.

Honestly, I feel like I didn’t tweet that much before the pandemic. Then suddenly, I was home all the time not seeing anyone, except my partner, so I feel like that was sort of it.

I have a ton of nostalgia for Livejournal, which was my first internet space. I’m just used to saying my thoughts on the internet, and Twitter has turned out to be a really great space for that. [Bettina and Sarah laugh.]

I feel like it’s both the best and the worst space for it. I’m scared of the worst space, so I don’t even try to go into the best space.

I don’t know what 2021 holds, in terms of a return to a life in which we can return to being with each other, but do you see next year being a year where you want to be in more physical presence with your Filipino identity? If the online space feels really rich right now, do you feel like the real world space will be equally rich in that way?

Yeah, absolutely.

I mean, I feel like if there’s anything this moment has made me realize, it’s how much I regret not finding physical space with people more when I moved to New York. I was always like, “I need to have a housewarming party,” and I kept pushing it back for various reasons, like, “Oh, I don’t have enough chairs in my apartment.” [Sarah laughs.]

Now, I’m realizing that a lot of those excuses don’t actually matter. When we can gather again, people will just want to be together. I don’t think people will care very much about the number of chairs I have in my living room.

Sign up for Currantly, our newsletter delivering original food stories and news analysis, with surprise treats of freshly curated recipes and product drops. Think of it as your monthlyish digest to deepen your stance on food issues and be creatively inspired.

Sarah Cooke is a freelance writer and reporter based in Washington, D.C. Her reporting, which explores the intersection of food, culture, and power, has appeared in DCist, Eater DC, and Washington City Paper.

Sign up for Currantly, our monthlyish newsletter delivering original food stories and news analysis, plus fresh curations of recipes and product drops.