INTERVIEW

Alicia Kennedy on Ethical Food Media, Patti Smith, and Goat Cheese Omelettes

WORDS BY SARAH COOKE

PHOTOS COURTESY OF ALICIA KENNEDY

NOVEMBER 12, 2020

Alicia Kennedy is a writer based in San Juan, Puerto Rico. She writes a weekly newsletter on food culture, politics, and media, and she is at work on a book about veganism and capitalism for Beacon Press.

This interview, held on October 13, 2020, has been condensed and edited for clarity. On the cutting room floor: why copywriting is so important, Yotam Ottolenghi’s latest cookbook, and Sarah’s bad internet connection.

Sarah: What were your professional hopes and dreams for 2020, and how has COVID affected them?

Alicia: I had wanted to travel around the Carribean more this year, to do more research into sugar and rum and ideas of sustainability around the Caribbean. I really wanted to go to Cuba, I really wanted to go to the Domican Republic, I wanted to go to smaller islands like St. Croix, and I wanted to return to Barbados, but that didn’t happen.

For me, COVID in a way saved my professional ambitions as a writer, because I don’t think what I wanted to do was going to work out financially. My stable income dropped 80% from January to May. But I was able to benefit from the CARES Act because it was available to freelancers, and that completely changed in my life, in that I was able to actually calm down.

I started working when I was 15, so I feel like I haven't had any time to think for the last 20 years. I decided to spend the time reading, thinking, and continuing to write my newsletter, which ended up turning into a stable (for now) income, which I didn’t expect. I don’t think it would have happened without the pandemic, which is really complicated. It’s fucked up that I was able to breathe for the first time in 20 years because of the CARES Act.

For the moment, I’ve been able to somehow escape the true, true burdens of capitalism as a human being, and that is what makes me so attached to how necessary it is for everyone to have the ability. To have that escape from wage labor, those moments of getting the monkey of capitalism off your shoulders, is just so essential to continuing to be a human being.

If COVID hadn’t happened, I don’t know what I would be doing right now, because I wouldn’t have had that time to think with the money from the government. And I don’t know if people would have been as receptive to what I was doing in my newsletter. I can’t fathom what the year would have looked like otherwise. But it’s really complicated to be grateful for how it turned out, because it is a terrible, terrible, awful thing.

Because the [hospitality] industry is dying, I don’t know how I would have continued to make money. When the pandemic started, I did a lot of reporting on labor and restaurants, but that wasn’t a sustainable thing for me to keep doing, because I was really going a bit mad. It was emotionally taxing. I have the utmost respect for any journalist who continues to cover all these really, really emotionally taxing things while also being emotionally taxed themselves.

I think that unfortunately, we were on the road to experiencing a disaster of this magnitude for myriad reasons. Journalism and media needed the moment of reckoning that is happening, in terms of competition from independent outlets and chickens coming home to roost or out different editors who have been toxic.

Are there models of media or journalism that are less toxic and more equitable that you would like to see more of in the future?

The model that everyone should bring up is Whetstone, but that’s because what it’s started is great. Vittles is also really great.

I would hope to see more cooperative worker-owned models of media; I think that’s really the only way to go. Broadly speaking, I think it’s wonderful to see people unionizing at larger media outlets. That’s long overdue and necessary.

All these movements towards unionizing, towards worker-owned media, towards independent media owned by people who really have a stake in the work that they’re doing: I think those are all really good.

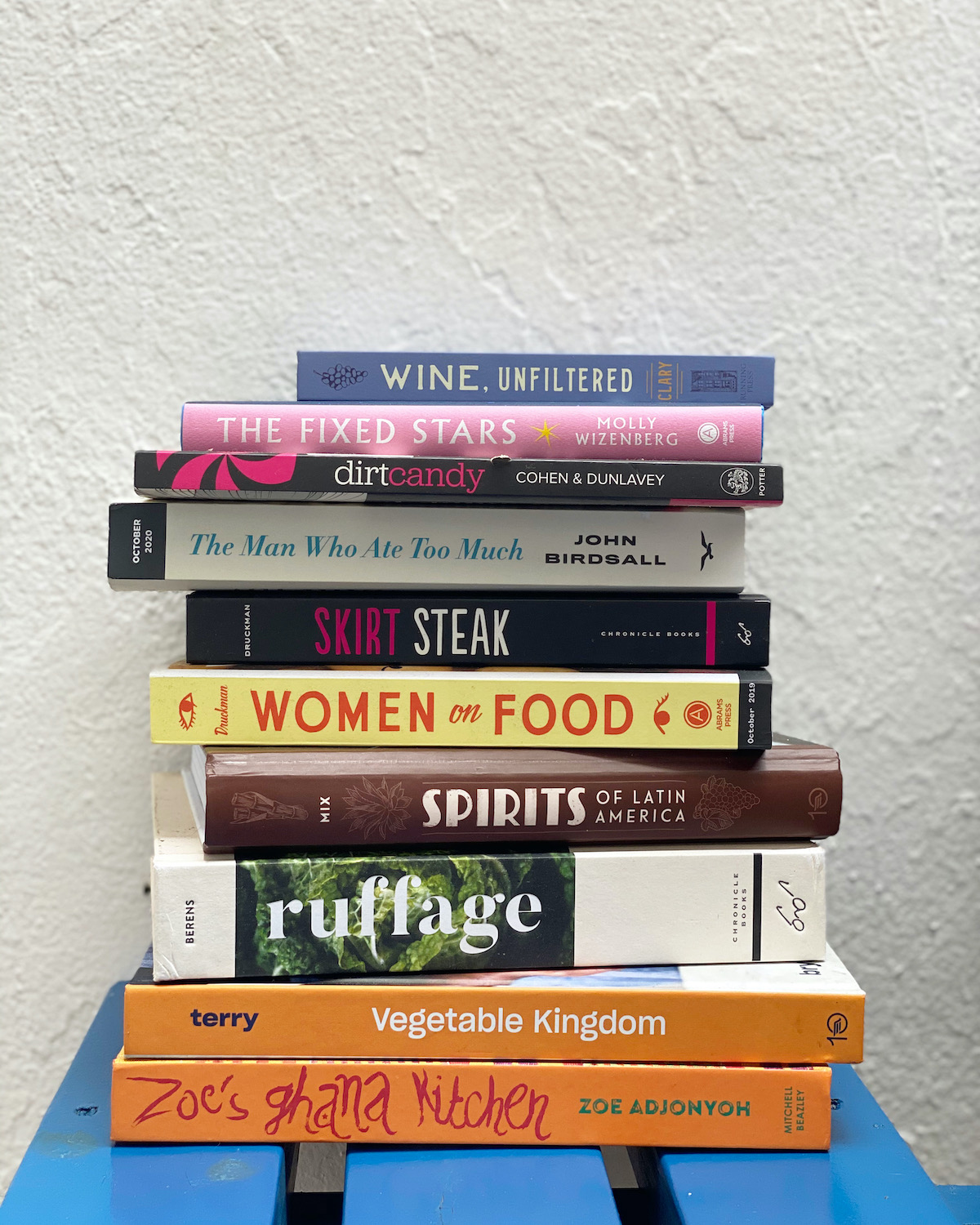

From Alicia's personal cookbook collection. Alicia Kennedy

How did you get into writing about food and your specific areas of food writing?

I used to write about literature and books. When I became vegan in 2011, I got really into baking, how the science of it worked and how to make things actually taste good. I kind of accidentally started a vegan bakery that I ran for just a year from Long Island. Then some personal issues happened, and I was at a point where I was so exhausted from working full time and doing the bakery that something had to give, and it was the bakery.

Because I had this experience running a tiny artisanal food business, I thought, “Maybe I could write about food.” I started writing about food in 2015, covering vegan stuff specifically. In the middle of 2015, I left New York magazine, and then I went to Food & Wine for a six-month contract. After that, I went to Edible Brooklyn and Edible Manhattan, working part time. Since 2016, I’ve more or less been making my living freelancing.

I don’t know how I specifically decided to cover food the way I do, except that it all stems from having been vegan, having run a small food business, having worked at Starbucks. I also worked at a wine bar in the East Village, and I had also done a lot of events with chefs, so from the beginning I had an understanding of sourcing food and ingredients, of where sugar and chocolate comes from, and of animal welfare. I’d also been reporting from Puerto Rico since 2016, so I had this understanding of food sovereignty and the way that colonialism and policy affect food.

I didn’t make any conscious choice to cover food the way I do. I just have always thought there’s this gap, but it’s not a gap that’s there in coverage because people don’t know it’s there; it’s a gap that’s there on purpose. I think that’s just become my thing, and it’s this year that I’ve gotten super vocal about how much I hate the way most food issues are covered.

I wrote a piece for the New Republic in February about the ways in which climate change is or isn’t addressed in food media and how policy issues could be addressed in one section of the publication, but the food section will be completely frivolous instead. And I think that was the start of my deciding to do cultural criticism within food, instead of straight up just trying to be a journalist. I like doing cultural criticism, because there’s more focus on the act of writing, which I really missed while doing straight food and beverage stuff.

I mean, this sounds so pretentious [Sarah and Alicia laugh] but I started out writing about books, about literature, really caring about writing on a sentence level. Being able to care about that again is very nice. It’s really interesting: I started doing the kind of writing I do in the newsletter because there wasn’t space for me to do that anywhere else, really, except in political magazines, but they paid such garbage. No one else was letting me sound like myself, or write the way that I like to write. I felt so, so not able to have a voice, a writing voice, in what I was doing.

Now that I just decided to say fuck it and publish that writing myself, other people are like, “Oh, that’s what Alicia sounds like, okay. She can write for us now.” [Both laugh.]

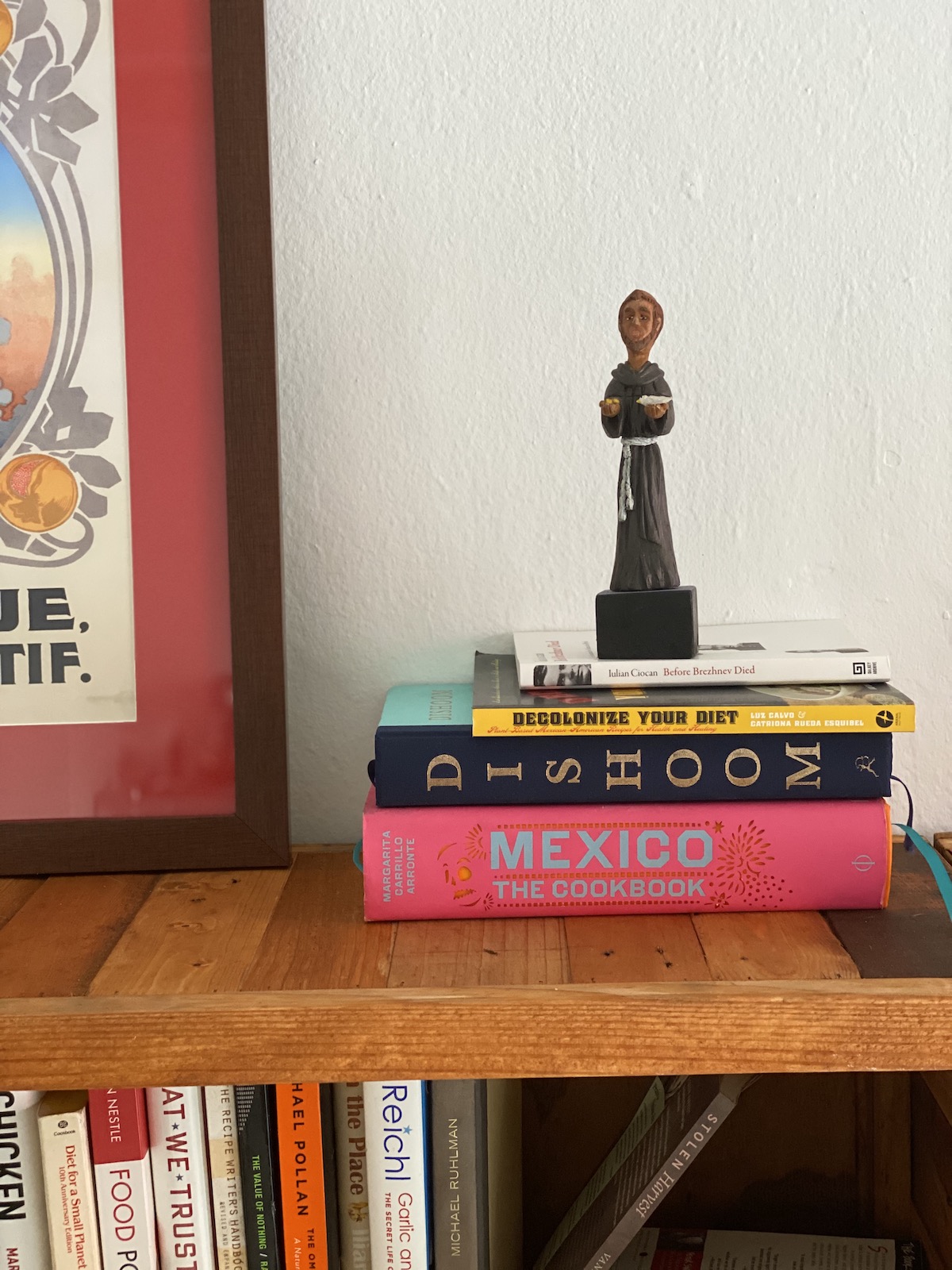

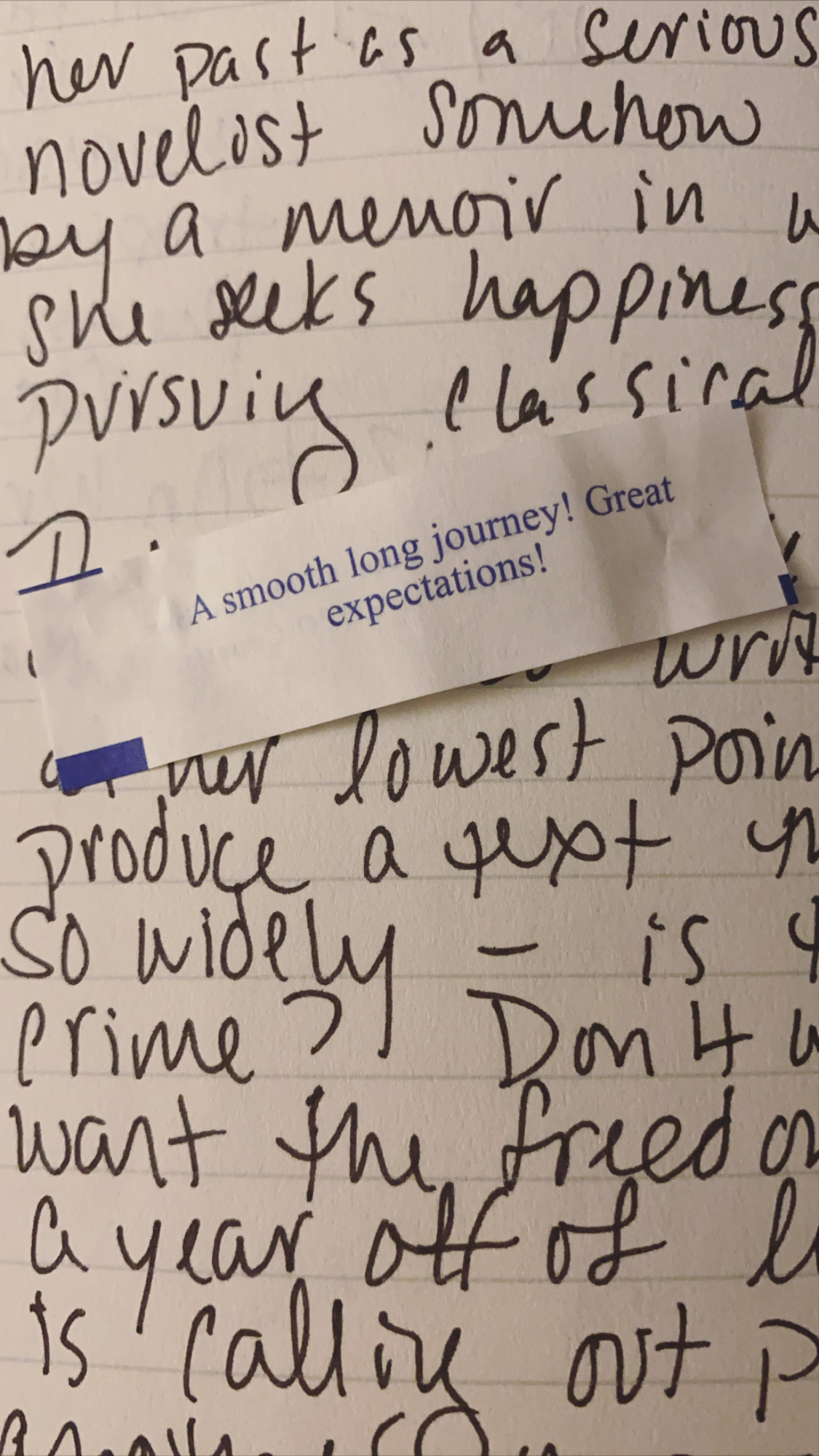

At work. Alicia Kennedy

Reading your newsletter was one of the things that made me see you can write about food through a lens of writing. Seeing in your writing such attention not only to subject matter and your perspective, and also to your voice—it’s so compelling.

Since you have previously lived in New York, and now you live in Puerto Rico, I’m curious: How has where you lived affected what you write? Not necessarily what you write, but how you feel as a writer, how you feel your voice comes across.

Recently, I was reading Patti Smith, which I’m always doing, because she is really my model as a human being, as a creative bridge. She’s so cool, and she’s so iconic, but she still embodies such an earnest enthusiasm for life and for art and for the spiritual and for her work and for literature. Everything.

That earnest enthusiasm is, I think, what I have from growing up in the suburbs, and I think that hopefully comes through in my voice as a writer too, which is that I’m not cynical. I mean, I am a little bit, but I’m not really cynical. I’m very, very hopeful and just want things to be good and better, and better for everybody. I want everybody to live their life to the fullest.

Even when I was living in the city, and even though I went to college in the city, you never get rid of being from the suburbs. And you especially never get rid of being from right outside New York City and looking in. It’s something that kind of stains your soul [Alicia and Sarah laugh], and you never get rid of it.

I think that I always have this kind of chip on my shoulder about people thinking that they’re too cool for school, to use a stupid phrase. That definitely still has an impact on my writing, where I want people who are stuck in that mindset—“I’m in New York, and it’s better than everywhere else in the world!”—to be able to get over that, because it causes this perspective that is so myopic and awful, especially in food media, where people act like they’re just not in reality at all.

And then of course, living in Puerto Rico changes my writing, because I’m just way more aware of myself as a person from New York, as well as a person who can’t communicate to people the way I want to communicate to people all the time. When I take my first sip of coffee, and I want to say, like, “Oh, this is so fucking good, this is the best fucking part of my day,’” I could say that in Spanish, like, “¡Qué rico!” but it just wouldn’t be the same.

That phrase feels like something that doesn’t come from my body or from me as a human being. I mean, this is the struggle of anyone who has tried to communicate in a second language, right: I don’t know who I am in this language. Because how do you be yourself in a language that you have more of an intellectual than physical understanding of?

Basically, because I’m in Puerto Rico, I understand the limits of communication in a better way. Even if I’m speaking English to somebody for whom English is a second language, they’re not hearing me the way probably that you’re hearing me, or they’re not hearing me the way that my friends in New York hear me. And so it’s this understanding of how tied to myself by voices I am, and how everyone’s voice is so specific and very rich and significant.

By doing the writing that I’m doing from [Puerto Rico], I’m just far more aware of that, and I’m far more aware of how much I want to retain the specificity of my own voice, because it’s not always legible to everybody. The idea that because my voice is just not always transferable—it makes me a lot more possessive of my voice, I suppose.

The faces of a voice. Alicia Kennedy

Right now, I’m very slowly learning Spanish. It’s like I’m going through a closet and trying to find the right coat, but none of the coats are right; and yet, that’s what I’m working with.

I loved your two part series about traveling and how you navigate the various ethics involved. You wrote, “You can’t overcome yourself, but you can adjust your gaze.” To me, that is such a generous offering to readers and to people, in terms of what I see as an enduring belief in the capacity to change. Do you feel that is part of your ethics?

I do. I think everyone can change. I was just thinking today about how if I could erase the first 25 years of my life, I would. [Alicia and Sarah laugh.] I think because of the pandemic, every weird and stupid and bad thing I’ve done is coming to the forefront of my brain.

I’m also thinking about cancel culture, and how I really, really believe in people being able to change. That goes back to what I was saying about Patti Smith and being enamored of the world all the time: I think it would be a really, really sad thing to go through life thinking people can’t change. I know how much I’ve changed as a thinker and a human being in the course of my life, and I think that the best thing that travel gives people is a chance to change their gaze.

I think so much of my writing is just wanting people to stop thinking that their perspective is the absolute perspective. Plurality is the word that I keep coming back to more and more lately: It’s wanting to understand the plurality and specificity of every human being’s life and how that creates who they are, and also how much capacity— if you’re aware of it—that gives you to understand and change your perspective.

It’s just so important to understand who you are in the world and what you represent in the world, even the bad things. Being from the US, I represent imperialism, and English is my only fluent language, really, and that represents imperialism as well. And my whiteness, whether someone interprets me as white or whether someone interprets me as something else, means something else around the world.

It’s understanding context and going from there and not being afraid to make mistakes. Not having that really touchy relationship to the most superficial aspects of identity that people are going to understand you as—just accepting it and understanding how you can be a better person despite that, in whatever context you are.

I say not being afraid to make mistakes, but I’m fucking terrified to make mistakes all the time.

Same.

You know, I’m terrified of just saying the wrong thing, making grammatical errors. And so I understand it, but at the same time, you have to be able to live with yourself and also change yourself.

Alicia Kennedy

I think especially for writers, as you generate a backlog, it’s almost like each piece is a marker of who you’ve been. It’s humbling.

Yesterday, while I was prepping for our interview, I made the clementine cake from Nigella Lawson’s How to Be A Domestic Goddess. You’ve written about your own relationship with that book and idea of “being a domestic goddess. I loved that piece, and I wanted to draw out what you highlight as the false choice between domesticity and independence. For you right now, what does domesticity look and feel like?

[Alicia laughs.] You caught me at a weird time. In the beginning of the pandemic, I was cooking so much, and now, I don’t want to cook at all.

On Instagram, once I got over 4,000 or 5,000 followers, my tone shifted. It’s added this new layer to what you’re talking about, in regards to the false choice between domesticity and independence, because now I’m also a performer for other people of my domesticity or lack thereof.

My boyfriend used to be a bartender, and we’ve basically lived together since we started dating. But I didn’t know that he had never chopped an onion before.

What? [Sarah laughs.]

As of a year ago, he had never chopped an onion in his life, and I was like, “Holy shit.” [Alicia laughs.] Since the pandemic, he’s gotten into making bread, stuff like that. But the funny thing about it is that he’ll be doing one thing in the kitchen, and I’ll be making everything else that goes along with it. But his presence in the kitchen as a newer cook is so overpowering that you would think he was doing all of it.

I did feel like I lost something when he learned how to cook a little bit, in terms of my control of the kitchen, which is something else from domesticity. I lost some sort of magic by him learning how to cook a little bit, I think, and that’s a weird thing, because I didn’t anticipate ever feeling that way.

Nevertheless, if I ask him to make the toast or the oatmeal for breakfast, it’s a disaster, but I don’t care, I love him. [Sarah laughs]. I call him the beverage director of the house; he’s the sommelier, the bartender, and I think that’s sufficient. I don’t know what I would do if I had been locked up with someone who couldn’t make me a martini. [Both laugh.]

But also, I’m very bored of cooking, just so bored, and I know everyone is. Takeout doesn’t have the same feeling of relief as going somewhere and having interactions. Here in San Juan, we know all the bartenders and chefs, so everywhere we go we would have a nice interaction with people. Losing that, and losing that third space of shedding the work, life, that’s been really taxing.

The pandemic has killed a lot of my fantasies about being self-sustaining completely. If I didn’t have to worry about money, would I like to cook all my meals? Sure, because all I’d be doing all day would be reading, and then I would get up and cook. And that would be my life, and that would be great. But because that isn’t my life, I need the outlet and relief of that third space, which has been lost to all of us right now for the most part—and when we’re in a third space now, it’s fraught with tension and fear.

Moving briefly into your book: Without spoiling any of the work you’re doing on it, what’s exciting about it right now, about the research and the connections you’re making?

[Alicia laughs.] It’s the first time I feel like I have imposter syndrome in my life. It’s the hardest thing I've ever done, but I also keep telling myself that writing a book should be the hardest thing I’ve ever done. It feels like a thing that’s over my head and I have to get right and then I have to get perfect. When you finally get what you want, it’s like, Oh my God, am I really up to this?

The research is exciting, because I am making new connections, and I am seeing that my thesis is correct. And that is very nice, but at the same time, I have this idea in my head that my voice isn’t serious enough for the subject matter and for a book. But I know that’s not true. It’s just a lot of messy emotions, frankly, about finally getting something that I’ve wanted for so long: to write a book about veganism, which is the thing that has given me so much in my life and has been so, so generous to me as an ideology, as a lifestyle, as everything. Wanting to do that justice is daunting and intellectually taxing. Wanting to get it right and prove myself: It’s a lot. It’s just a lot. [Alicia laughs.]

Some people think that getting a book deal is the end all be all. I mean, going into it, I knew it wasn’t, but at the same time, I was like, “This is something I want, this is something I’m ready for, this is something I’ve been training for.” It is very stressful, and I want to be honest about that. Because I think it’s valuable to be honest when people think you have it all together or figured out, and it’s like, absolutely friggin not. [Alicia laughs.]

I really had in my head ideas about going to different places and different restaurants that I haven’t been to, doing research and reporting and having atmosphere to draw on while writing the book. I thought the process of writing the book would be more organic in terms of the research and the reporting, but because we’re in a pandemic, it’s impossible for me to do that. Like, I’m just in my house with a bunch of books. [Both laugh.] It’s really hard to create atmosphere out of that.

I mean, I think the atmosphere just feels toxic right now for such a variety of reasons.

I’m in a big limbo of what the world is going to look like when [the book] comes out in two years. The fact that I’m writing a book that might be irrelevant for a different world is really difficult. I don’t know what the world will look like, I don’t know what it will feel like. I just don’t know. I put little stock in presidential politics, especially because I live in a colony, but if Biden wins, my book is going to feel different than if Trump wins.

And I don’t know what the world’s gonna be like in terms of hospitality, in terms of food, when there’s a vaccine, if there’s a vaccine. It’s just really, really hard. I thought the hardest thing would be that I sold [the book] during the pandemic, and so I couldn’t celebrate in the way that I wanted to; like, I’d always assumed I would go out and do a million shots. [Sarah laughs.] Now, because that didn’t happen, and I’m starting to write it, I’m like, Holy shit, I expected to be able to do so much, and I don’t know what’s gonna happen.

My last question is actually about your dog, Benny, who I think should be a dog influencer on Instagram. If Benny were a human, what is a recipe or a dish that you feel best captures his spirit?

As a dog, he is a perfect French omelette made with exquisite grass-fed butter, with soft, fluffy eggs, and stuffed with goat’s cheese. That’s his personality, because he’s decadent, he’s just a prince. We call him a prince all the time, but he really is. He wouldn’t know any other way to live.

Prince Benny. Alicia Kennedy

Sign up for Currantly, our newsletter delivering original food stories and news analysis, with surprise treats of freshly curated recipes and product drops. Think of it as your monthlyish digest to deepen your stance on food issues and be creatively inspired.

Sarah Cooke is a freelance writer and reporter based in Washington, D.C. Her reporting, which explores the intersection of food, culture, and power, has appeared in DCist, Eater DC, and Washington City Paper.

Sign up for Currantly, our monthlyish newsletter delivering original food stories and news analysis, plus fresh curations of recipes and product drops.