INTERVIEW

Jonathan Nunn on London, the Power of the Margins, and Cookie Monster's Greed

WRITTEN BY SARAH COOKE

PHOTOS BY JONATHAN NUNN

JANUARY 21, 2021

Jonathan Nunn is a food and city writer based in London, and the editor of Vittles. This interview, held on December 2, 2020, has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Sarah: How are you feeling about 2021? What’s on your mind, and what are you looking forward to?

Jonathan: When the first lockdown happened [in March 2020], it did feel like we were on the cusp of something. I know we kept saying nothing’s really going to change, but the feeling that we all needed to be constantly producing stopped, for me at least, and there was still that faint glimmer of hope that things would change.

When lockdown was lifted, it felt very clear that business was going back to what it was before. I almost felt like, “How bad do things have to get before people actually really want change?” Cause it’s going to have to get much worse than this.

So I think first of all, my priority as a writer and as an editor is to try and keep up that same energy from the early days of when we were talking about this nonstop: Things had to happen, things had to change. Because it’s very easy to become ground down by this new routine of ‘business like before, but worse’.

My general feeling is not particularly one of optimism in terms of how legacy food media is going. In April, I wrote an article in The Guardian on how the problems with restaurants weren’t caused by the pandemic, that there were structural issues that existed before the pandemic, and how this would be a good time to reimagine what the idea of a restaurant was. It’s very clear that legacy food media here will not cover those issues. Either they don’t want to, or they don’t have the flexibility to think in that way.

But I think there is a lot of optimism as to what is happening on the margins of food media. I think one thing which I feel more at peace about now is that actually, perhaps necessarily, the writing that I and people like me are doing maybe has to be on the margins. Before I think I wasted a lot of energy being annoyed that these conversations aren’t more mainstream, but the margins can be a powerful position to be in, especially in that it means the work never stays still or becomes complacent.

I think at the moment you see all these islands popping up on the margins of food media, whether it’s Alicia [Kennedy]’s newsletter, Sourced, In Digestion, or Whetstone, which has been around for a longer time. The rise of Indian food media is really incredible. You see a lot of young, politically engaged Indian writers now using food writing as the easiest way of talking about what’s happening in India right now, and how that’s a continuation of colonialist policies.

You see these little islands, and as the sea recedes, it will become sort of more of a continent, and I think you’ll see those little pockets joining. So I’m quite optimistic in that sense, that those forces on the margins will be a much bigger force in 2021.

Do you feel that since March, when Vittles debuted, there’s been an increasing influence on legacy food media? Or are you more interested in building the island out, as it were, and making it more spacious for people who want to be part of the island?

I think both. Without trying to build Vittles up too much, I think you can see a small effect on certain parts of legacy food media, and I think that always has to be a part of it. That is part of opening up the space as well—to open up that space in legacy food media for certain writers who might want to write for me but would also want their work to be published by a bigger publication.

I think a great template here is gal-dem, which is a publication that is still on the margins but has influenced the legacy space on its own terms, giving their writers much more opportunity but still remaining radical in their approach. And hopefully, they’ll be the legacy writers and editors of tomorrow.

I see that happening more, but that is obviously constrained by the fact that these papers are huge institutions. I liken it to a massive cruise ship: Certain cruise ships are banned from going up the English Channel, because they can’t turn fast enough when something goes wrong. And I see some of the papers like that. Some of them know which way they have to turn, but the apparatus is too unwieldy to actually turn, so they’re more content running it onto the rocks.

One example that I quite like, even though it’s quite a weird example, is UKIP in the UK, which is this very reactionary, far-right party. They didn’t win a single seat in the UK Parliament, but by tormenting the Conservative party who were slightly to the left of them but still very much on the right, they managed to have this outsized effect on British politics, from Brexit itself to the current trajectory of the Conservative party.

Without emulating anything else about UKIP [Sarah laughs], that is quite a big lesson for anyone, and especially the Left, to learn. You see it happening with the Democratic Socialists of America, that there is a big role in trying to pull those bigger machines to the way you would want them to be. So while I can’t pay too much attention to what the rest of the food media is doing, I do see that part of Vittles’ purpose is doing that.

What differences do you see between American and British food media, if you do see them? I think this question of legacy food media—it’s so true on both sides, and I think some of the same structural issues exist in both.

There is a difference. I don’t necessarily think it’s the difference that people think it is, though. It also varies as to what you’re talking about when you say food media, because the part I’m most familiar with is the part I specialize in, which is restaurant writing.

I think there’s a very simplistic notion that British restaurant writing is about being entertaining, and American restaurant writing is about being correct. That’s a very simplistic dichotomy, because I think you can be both, and I think the best writers have always been both.

There’s a lot of truth that the difference with restaurant writing is that American restaurant writing has always been tied to cities, whereas in the UK, we have one city paper in London (a Tory rag called the Evening Standard) and the rest is national. When you’re doing national food writing, you kind of have to assume that most people aren’t going to go to the restaurant you’re recommending; so it then becomes more about the prose itself.

That is a weakness and a potential strength. I think one interesting thing about British restaurant writing is that because there is this assumption most people won’t go, it’s always been rooted in the satirical. The critic is in this position of describing these very grand restaurants. and I think there’s always an element of satire about the way the British upper-class eat.

“Before I think I wasted a lot of energy being annoyed that these conversations aren’t more mainstream, but the margins can be a powerful position to be in, especially in that it means the work never stays still or becomes complacent.”

I wrote about this recently, using the example of Jonathan Meades and A.A. Gill, who were very powerful critics during the 90s. What they were writing about was very much a reaction to the birth of what we now see as new British cuisine; they satirized some of the pomposity and pretentiousness that surrounded it.

That’s a really interesting legacy of British restaurant writing, for me, and I would say it’s something that I’ve probably sustained in my own writing, albeit unconsciously. Like, from the very start, it was just quite obvious to me that food writing should be funny, even if I didn’t know where that came from. I’m just satirizing different things. But where I think British restaurant writing has gone wrong, and this is something that should be leveled at Gill especially, but also Meades and many others, is that too often the satire punches down, rather than up. And that’s when you get critics veering into territory that I would classify uncomplicatedly as racist, classist and fatphobic.

What’s funny though, is that when I started writing two and a half years ago, my writing was very quickly characterized as American in style, even by my own editor. He said something very nice when I wrote my first article—he compared it to Jonathan Gold and Robert Sietsema, who are writers, especially Gold, who I admire.

But I hope what I do is quite different from those writers. I don’t want to be Jonathan Gold. What we are writing about may be a similar type of restaurant, but it’s for different reasons, and with a different perspective.

When you spoke with Alicia Kennedy for her newsletter, you described yourself as a city writer as much as a food writer. How has London, or other places that you’ve lived, shaped you as a writer?

There’s a great line in Invisible Cities by Italo Calvino, where Khan asks Marco Polo why he hasn't mentioned Venice yet, even though it’s his home city. He says, “Everytime I talk of cities, I talk about Venice.” And I feel like in my writing, it’s always talking about London, even if there are times it doesn’t mention it explicitly.

Getting into food writing was a way of me trying to talk about London and the way London is changing in a way that made sense to me through the lens of something that I knew very well.

It’s a city that I’ve lived in all my life, with the exception of three years at university. I was born in Homerton Hospital in East London, I grew up in Stoke-Newington, lived in Stamford Hill, then Bounds Green, which is this very common London move into Zone 4 suburbia. Very, very rarely can I see myself anywhere but here.

I’ve had relationships dissolve because I’ve been unwilling to move across the country. [Sarah laughs.] I don’t even know what my writing would like without London anchoring it.

My dad was born here; he’s white British raised by East End Cockneys. My mum’s side of the family is in Goa, and she came here from Kenya in the 1970s. So that’s old London and new London right there. There’s that very clichéd idea of the second generation immigrant who feels that they’re stuck between two worlds, but I’ve never ever felt that way, because I’ve always defined myself as being from London before being British, before being Indian or being Goan, before being European.

I’ve always thought of myself as a Londoner, first and foremost, and I think that sense of identity has grown as I’ve got older and as politics change. Increasingly, London is becoming this island of leftist thought and multiculturalism in a kind of blue sea of reactionary middle England. I often do not feel much connection to the rest of Britain for that reason.

I would say that London is very important to me, because I think it allows me to make sense of my identity—the way that I speak, the words that I use, they’re influenced by not just white cockneys but by the Black Afro-Carribean diaspora, by South Asian Muslims, by Eastern European Jews. London is a very mixed-up city by definition, and that kind of fits in with my mixed-up identity as well.

“There’s a great line in Invisible Cities by Italo Calvino, where Khan asks Marco Polo why he hasn't mentioned Venice yet, even though it’s his home city. He says, “Everytime I talk of cities, I talk about Venice.” And I feel like in my writing, it’s always talking about London.”

Did you always know you wanted to be a writer?

Not at all. I studied maths at university. I told someone this the other day, and they were like, “I realize I don’t know really anything about you.” [Sarah laughs.]

I went to university fairly certain about studying maths, and I left absolutely hating it. I ended up going to way more film studies lectures than my own lectures.

It really wasn’t until I was 24 or 25 when friends would always come up for food recommendations, and they were like, “Why haven’t you started a blog?” At that time, it was in the mid-2010s, and blogging was the way to get yourself known. I had all these blog ideas, and I just never did it; up until 29, I was thinking it was probably never going to happen.

My “origin story” is very strange, because it wasn’t through blogging or writing a book or being discovered on a forum. It was just shitposting on left Twitter. [Sarah laughs.] I got a commission from Eater via George Reynolds, who is a friend and a great food writer. I didn’t know him then, but he DMed me and asked if I wanted to write a short piece for Eater London, because it was clear from my Twitter I liked food. He had no idea at the time that I really wanted to do that.

I think he sold me to my editor Adam as, “I don’t know him, but he wrote one of my favorite tweets of all time,” which was a tweet insinuating that Jamie Oliver would ban eating ass. [Sarah bursts out laughing.]

That is kind of how it all started. It felt like a series of mistakes that I got into it, and I still have to pinch myself that I am writing, because I never truly thought it was going to happen. I’m not a particularly refined writer, as in I still, through the act of editing, am learning a huge amount about writing and the technicalities of writing.

One of the nicest things which someone said about me, another writer who I admire, said that they felt I was a natural writer, which I took to mean that in a very sort of unpolished way, the way I write is quite intuitive and maybe conversational. And that helped me, because I’ve always straightjacketed myself as ‘a maths person’, not realising I didn’t have to be one thing or the other.

I still read other writers who are contemporaneous with me─people like George, or Ruby Tandoh or Thom Eagle─and feel like I could never write something as beautifully structured as theirs. Then I have to check myself and think, “Well, there’s a reason why people want to read you too, and it’s because you have a voice that is not like other people.” I think that’s the thing that every writer has to deal with: that sense they can’t write like the people they admire.

If you are someone who wants to have a gravestone, you should put “Jamie Oliver Wants to Ban Eating Ass” on it. I think that would be an absolutely amazing way to memorialize your time on Earth.

I wanted to ask your take on government support, or lack thereof, for the restaurant industry in London. Here in the United States, there is a complete lack of government support; healthcare is tied to unemployment, and there’s no wage replacement, no furlough scheme.

From your reporting, do you feel that the situation for restaurants is less dire in London than it is in the United States?

It is definitely less dire, from what I know about what’s happening over there. This is not to say that there aren’t a huge amount of bad things happening over here, and that the government’s response shouldn’t be heavily, heavily criticized for being both inept and inhumane.

But it’s a different ballgame when you’re talking about workers who do not have healthcare insurance—which is something from a British perspective that just seems entirely insane. From that life or death perspective, that is such a huge difference for us.

But again, that's something that was won from the margins. Socialised healthcare was trialled by a left wing municipal government in London a decade before it got national support. So I hope that keeps being pushed against. Even if the machine doesn't look like it will turn any time soon—I think it will eventually.

I think restaurants have had much more relief in terms of the furlough scheme, which has been maybe the government’s only big success during the pandemic. But there’s been a lot of missteps, and there’s so much more to sort out. There was the Eat Out to Help Out scheme, which was of course loved by restaurant owners who had the majority of news coverage; not so much for the restaurant workers. And now it looks like it was a huge health hazard too.

I know in the U.S., there’s this very big conversation on what restaurant writers should be writing about right now. We haven’t really had that, because people didn’t see the situation as dire enough.

I loved what you wrote in the announcement of Vittles Season 2.5: “I’m well aware that this landing in your inbox is an intimate privilege I have. In a world which is already depressing enough, I’m not sure it’s my job to always depress you further. I was so heartened by the reaction to last week’s regional chippy guide, which seemed to inspire what can only be described as ‘joy’ for a lot of people, even those who don’t normally read food writing.”

What does joy look like and feel like for you? And if you are finding it right now, where are you finding it?

I think what’s brought me the most joy over the last few months is the unexpected intimacy of being in a massive, sprawling city, and feeling like you’re actually in a village. I’ve generally had quite a hermit’s life for the last six months; it means that I’ve had to take pleasure in things which are a lot closer to home.

One thing that I feel like I need to do once I have more time is to get more involved within local community efforts and to feel like I’m giving something back. I feel like my writing can be a part of that, but it’s not enough to think that just writing about your area is any form of activism. It has to be physical.

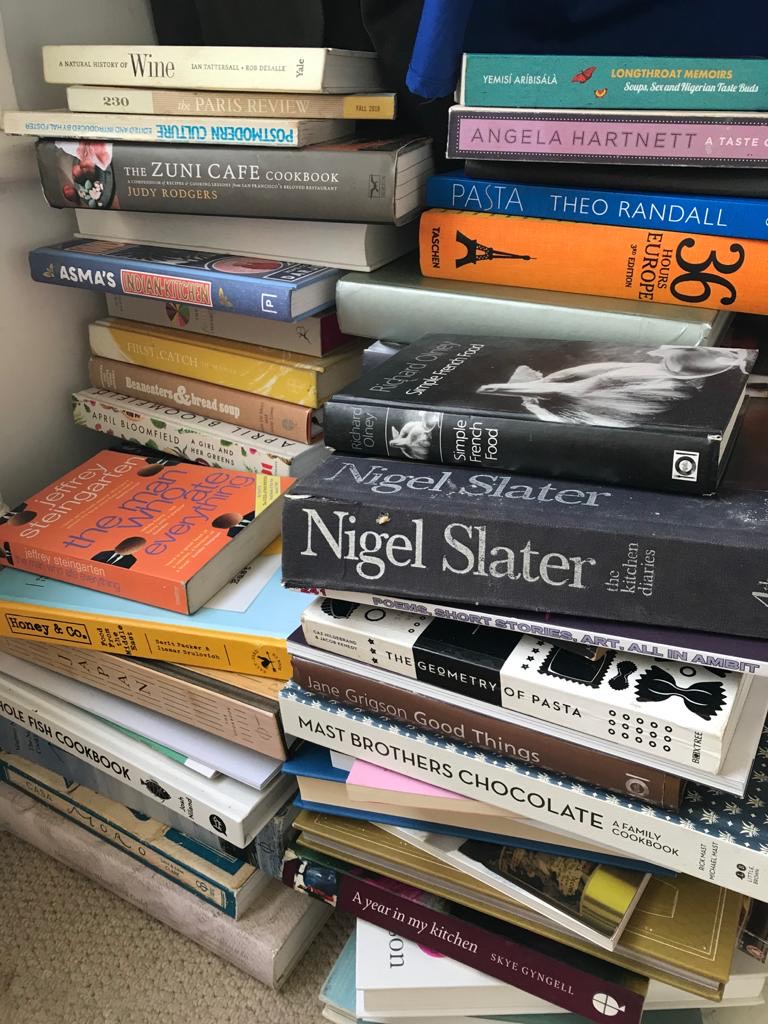

But given the level of busy I am, what gives me the most pleasure is to just actively take time out of my day to stop working and to think about what I’m doing. It could be as simple as taking the time to properly cook a meal for me and my partner, to lay the table properly. To take that time to be slow has been really good.

To get back into tea has been good as well, because tea is by its nature a slow product. I feel for a year or so, I wasn’t taking the time to enjoy tea the way I was before.

If you have had a go-to tea during the pandemic, what has it been? And is there a tea, or a type of tea, that you feel the most kinship with?

To be honest, the thing that I drink most is coffee. I feel like I need to drink coffee in a way that I don’t need to drink tea. I could survive without tea, because I just drink it when I feel like it; coffee, I need to drink it every morning.

In terms of what type of tea I like to drink, like food, as I get older, I just get more and more set in my ways about what I enjoy. When I got into tea, I would drink it constantly and I would drink everything, and now, I only really drink roasted oolongs and pu erh, almost nothing else outside of that.

The beginning of spring is a bit different. I feel like spring for me is synonymous with the new greener harvest, whether they’re Chinese green teas or first flush Darjeelings, and I feel like it’s important to have that at that time and feel that connection to time and the seasons, in the same way you would celebrate eating the first asparagus of the year.

In terms of what I drink it everyday, it’s teas that I find comfortable and gentle on the stomach. And you could probably tell from the second tea guide [that Nunn wrote for Vittles] that pu erh has a special place in my heart among teas. I feel like there’s a world and a whole way of thinking contained within pu erh tea that is fascinating to me.

I really want to start my own personal tastings with people outside of the tea industry, really with more people who are interested in food or wine, and bring them to tea in a way that they brought me to food and wine. I feel like with tea, there’d be a nice role reversal, where for once I’d actually be the expert in the room, and they would experience something for the first time that I might be able to teach them.

In a world where everything is possible again, I would love to do that. It sounds like a dream.

My last question is about the Swedish Chef, inspired by your piece in The Guardian about TV chefs. But is there something else you’d prefer to talk about? I realize that the Muppet Chef might not be a dream question.

The Muppets were actually slightly before my time, in that I don’t recall it being on TV when I was a child, but the Muppet I most relate to is the Cookie Monster. I admire the shameless commitment to greed.

Two years ago, I was in Japan for work. A tea farmer had taken us out to a Michelin-starred daikaya in Osaka, a stunning meal, and the chef was preparing everything in front of us. He said something to my boss in Japanese, looking at me, and then my boss elbowed me and said, “Stop eating so fast.” [Sarah bursts out laughing.] I think anyone who has eaten with me will recognize what I must have been doing at that time. I eat very, very quickly.

Sign up for Currantly, our newsletter delivering original food stories and news analysis, with surprise treats of freshly curated recipes and product drops. Think of it as your monthlyish digest to deepen your stance on food issues and be creatively inspired.

Sarah Cooke is a freelance writer and reporter based in Washington, D.C. Her reporting, which explores the intersection of food, culture, and power, has appeared in DCist, Eater DC, and Washington City Paper.

Sign up for Currantly, our monthlyish newsletter delivering original food stories and news analysis, plus fresh curations of recipes and product drops.